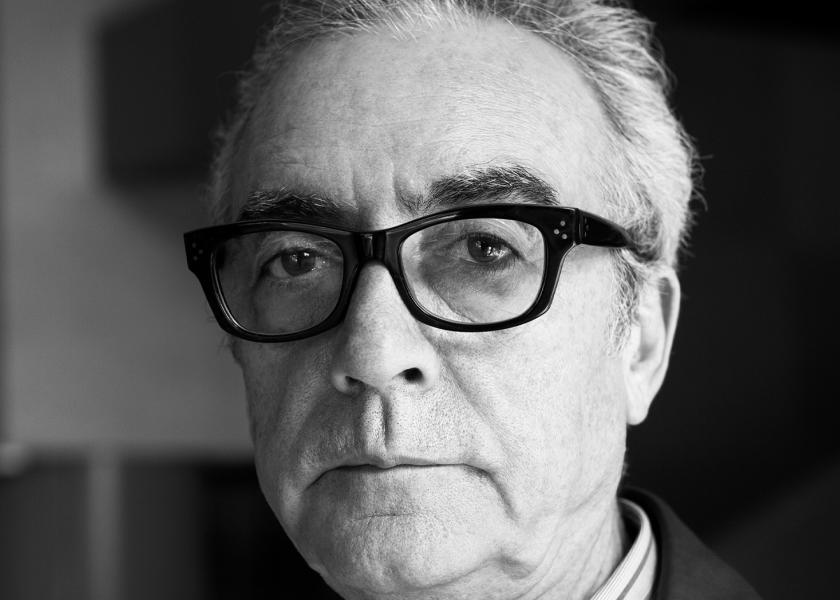

Sergio del Molino

“I Collect the Waste of History”

Few authors get their books on everyone's lips as soon as they hit bookshops. With a staggering ability to navigate at the juncture of fiction, essay and autobiography, writer and journalist Sergio del Molino will be at the helm of the Eñe Festival, which kicks off this week, with a focus on hybrid genres and disciplines revolving around the written word.

Sergio del Molino (Madrid, 1979) is one of those writers who manage to stir up feelings in readers, hopping from laughter to disillusion to irritation in just a few pages. If the chance arises, he can also strike a significant chord. “Writing to me is a way of being in the world, I do it every day. I write everything that worries and amuses me, whether in an article, a book or a little piece for a newspaper,” he says.

The literary scene became aware of his name in 2009, the year del Molino, a regular contributor to El País and Onda Cero, published the short-story book Malas influencias (Tropo Editores) and the essay Soldados en el jardín de la paz (Prames), a journalistic report of sorts about a German colony settled in Zaragoza, the city where he resides. But it wasn’t until 2012 that Sergio del Molino would make a grand entrance in the Spanish literary scene, thanks to his debut novel No habrá enemigo (Tropo Editores), picked that same year as one of the ten most recommended books by the guild of Spanish booksellers.

This leap in his career was followed up a year later by his major work so far, La hora violeta (Literatura Random House), an intimate and heart-breaking cry of pain (“written in a state of trance”) in which the Madrid-born recounts the last months of his son Pablo. “This is a very strange book, the one among all the books I’ve written I know least how to explain and the one I've had to talk more about,” he says. "I didn't write it to find a meaning or a moral, but to live through the sadness and the grief." Thanks to this book, El Cultural magazine named him among the twelve most promising Spanish novelists.

However, Sergio del Molino’s writing rarely revolves around his own experiences and the so-called fiction of the self--it fluctuates between genres, distancing himself from the purist style of other writers of his generation, merging history, fiction, biography and memoir to create what he calls “hybrid texts.” “Like all labels, this one serves to name the unclassifiable, an amorphous text that is not quite a novel. This is the kind of book that pisses critics off so much, because it’s not a novel nor an essay or a memoir. It’s a protest against those who always need a clear literary taxonomy. There’re many books that break away from that dynamic and which can be read as diaries, history books, essays or novels, becoming something unique that establishes a direct connection with the reader,” he explains.

Del Molino’s essays --for lack of a better label-- are a good example of this. La España vacía (Turner) is a journey through Spanish villages that lost all their population in the aftermath of the exodus to big cities between the 50s and 70s. In his recent Lugares fuera de sitio (Espasa), Del Molino seeks to decipher the anachronistic character of territories on borders that “spoil” the harmony of maps. “I’m interested in the marginal. I like to use history as material for my stories. I collect the waste of history; I gather the materials historians discard to bring them to the present and make literary croquettes with them. Some make palatial stews, but I’m more into using the leftovers,” he says.

“I gather the materials historians discard to bring them to the present and make literary croquettes with them”

These borderline texts are precisely the focus of the 11th edition of the Eñe Festival, held in Madrid and Malaga from 11-23 November. Sergio del Molino is this year’s director, following writers such as Antonio Lucas and Luisgé Martín. “These books break all the conventions of what we think we know about literature, going to the essence, creating a direct communication between the writer and the reader, between the one telling the story and the one listening to fall in love with it.”

We met him in Madrid, at La Fábrica, the event's organizing entity and the best place to interview a voice of contemporary literature such as Del Molino, to chat with him about his new phase at the head of this great celebration of literature, about the future of books, and about the sometimes seeming futility of literature