Paula Bonet

Stories by Brush and Pen

Literature, illustration, painting—the boundaries between disciplines have never been an obstacle for the versatile Paula Bonet to express her inner world. The coming days she will be at the Eñe Festival, which occupies a special place in her heart, with her show 'Abrir la boca y decir lo nuestro' [Open our mouths and say our thing], in which painting and live poetry go hand in hand.

Next Friday, 15 November, in the Ballroom of the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid, artist Paula Bonet (Vila-real, 1980) will be painting on stage for 60 minutes in a performance alongside Lara Moreno, who will be reading poetry, and guitarist Dani Llamas. The show is part of the Eñe Festival, one of the most important literary events in Spain.

Whether by brush or by keystroke, the main thing for Paula is to let out what she has inside. She feels social media, a key tool for many in her sector, have served her well when it comes to getting attention—there, she can freely display her illustrations. The same illustrations which, in addition to galleries and exhibitions the world over, also appear in many of the books she writes, such as Roedores (Random House Literature, 2018), La Sed (Lunwerg, 2016), or Qué hacer cuando en la pantalla aparece THE END (Lunwerg, 2014). However, her message is always the same: her own work, in which feminism plays a fundamental role.

What does it mean for you to come back to a literary festival like Eñe?

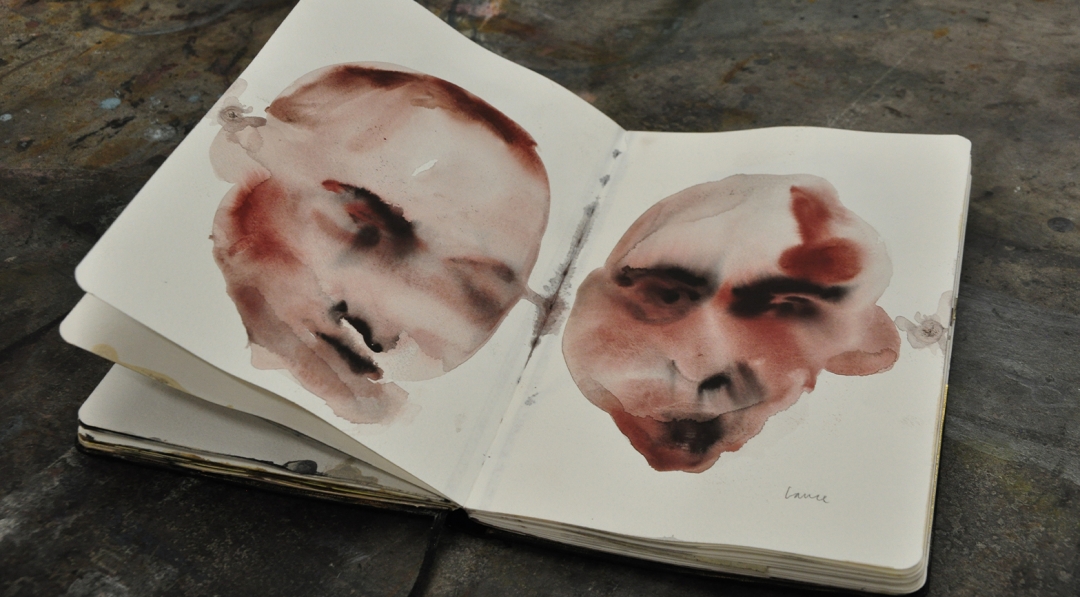

My first time was with Sara Morante and Sergio del Molino. I painted while Sergio read some of his texts. I already believed the Eñe Festival was an important event for the culture of this country, but when I participated in it, it became something that had a profound impact on my growth as an author. It was Eñe that pushed me out of my safe zone and the slow processes of the workshop, and into a new and head-spinning space. I took up improvisation, working in front of an audience and establishing a live dialogue between stain and word. To be able to participate in the festival again, and together with Lara Moreno, is a gift.

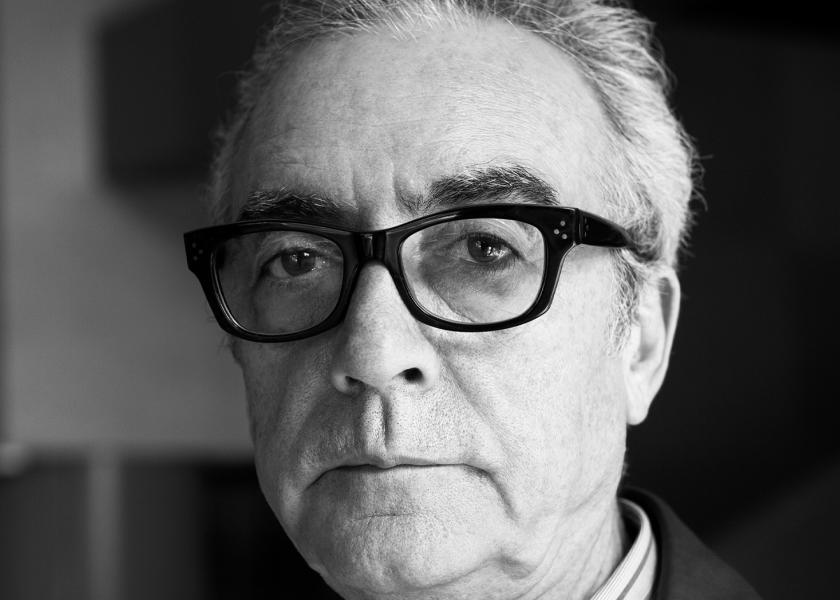

Paula Bonet is a writer, an illustrator, a painter— how do you define yourself?

I’m a storyteller. Sometimes I narrate with images, sometimes with words, and other times I participate in someone else’s narration with my illustrations. To me, images and words are communicative tools, in the same way that ballet or music can be. If I knew how to dance or had a minimum of talent on any musical instrument, I’m sure my tool palette would be richer.

Illustration from ‘Roedores’ by Paula Bonet. © Courtesy of Penguin Random House

How do you see that relationship between images and words you refer to?

As much closer than we would think. We’re an eminently visual society that doesn’t value images; we consume them at an appalling speed, and many of them have also been produced at that speed. I would ask the publishing world for more consideration with the images it prints. Sometimes I see pictures that give me a rash and make my soul hurt because of the lack of consideration; because they’re looking for the easy thrill, or because the only intention they have is to make lots of money.

“Female authors are speaking up, and many do so with great delicacy, commitment and talent. We are in a moment of vital importance for fiction”

What is the state of fiction in Spain right now, according to you?

Spanish literature is delivering great works. Many of them may not reach a mass audience, because most of the media insist in that same old patriarchal discourse we’re so tired of. But female writers are speaking up, and many are doing so with great delicacy, commitment and talent. This, coupled with the important fact that they’re telling what had not yet been told, leads us to conclude that we’re in a moment of vital importance.

Who are your big examples in literature?

There are so many of them: Mercé Rodoreda, Montserrat Roig, Lucía Baskaran, Belén Copegui, Carmen Martín Gaite, Nuria Labari, Cristina Morales, Lara Moreno, Laura Freixas, Rosa Montero, Christina Rosenvinge, Luna Miguel, the list goes on.

A notebook with paintings by Paula Bonet. © Courtesy of the artist

And in illustration?

I’m not a big follower of illustration. I am more the type that roams the art galleries. For example, I can’t go to Madrid and not visit Velázquez, Goya or Ribera.

What is talent, according to Paula Bonet?

It’s the greatest of traits. A gift that has to be cultivated and which is—hopefully—put to good social use. Although, who am I to dictate its use? Everyone can do with their talent whatever they want.

How have social networks influenced the artistic world in general? Do you think they help reinforce the message of books or illustrations?

When used right, they can be a good means of communication, but they can also be transformed into a great monster that cancels out, homogenises and swallows up. A few years ago, I used to follow the work of others on social networks, but I don’t anymore. The danger of longing to be appreciated and accumulate likes terrifies me. It causes me a great deal of unease to see fellow artists no longer knowing how to position their bodies—literally, with turns and folds—for photos, and worrying about combining their clothes in chromatic harmony with their work appearing blurred in the background. The work ends up being secondary and the maker becomes the focus for likes. I find it terrifying to see big brands using that private showcase in exchange for cash.

Personally, my use of social networks is quite simple and selfish, I use them as a showcase for my work. Once I’ve posted it, I don’t get involved too much.

“The danger of longing to be appreciated and accumulate likes terrifies me”

You are very active and vindicating, both with your work and outside it. You also teach several workshops. How do you think you can have a greater impact these days?

I would like to think both through my publications that come from pause and reflection and through the workshops I teach. Right now, I’m putting a lot of time and effort into a project called La Madriguera [‘The Burrow’], a painting and engraving workshop that I’ve started in Barcelona. We work etching, aquatint, soft varnish, algraphy and woodcutting, but we also work the word. We have students coming in from all over the world and, thanks to them, this workshop is not just a place of creation: it’s also a safe space for all of us women who are waking up and know that we will no longer ask for permission to name—and paint, and question—the world in feminine as well.