Ignasi Aballí

Filling the void

His work draws from Magritte, Duchamp, On Kawara and Michael Asher, among others. His elegant and minimalist conceptual art teases the audience to make them think. His latest project? The empty Spanish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, a project that, he admits, is the “most radical and most difficult” of his career, and which has been a “turning point”.

At a time of excess visual stimuli, conceptual artist Ignasi Aballí (Barcelona, 1958) advocates a simple world where the paradoxical use of common materials (dust, Tippex, fabric, newspaper cuttings, colour charts...) redesigns the meaning of life. His latest work, Correction, transforms the Spanish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale into a space devoid of works but full of antagonisms and concepts. A proposal that is both bold and original.

Correction recreates the Spanish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale within the pavilion itself but turning it 10o. How did the idea come about?

We considered making a specific project —more than taking ready-made works— for the pavilion within the context of the Biennale, that is, that only made sense there. Not long before starting to work on the idea, I’d finished another project where I worked with the architecture of the space, and it was on my mind. Combining both ideas led me to focus on how the Spanish Pavilion was built and located at the Biennale, slightly at an angle regarding its neighbours, and that gave me the key for the proposal: following the alignment of the adjacent buildings.

Does this “correction” have any political symbolism?

The proposal includes many interpretations, and one of them could be political, because I think all interesting artistic projects always have a political side that doesn’t need to be explicit, but that’s there, nevertheless. In this case, that “correction” of a national pavilion, which is like a symbolic space representing a country, somehow questions its memory and, even, its position regarding other countries, as well as the role of the pavilion itself within the exhibition or my own stance about participating in this Biennale.

“The proposal includes many interpretations, and one of them could be political, because I think all interesting artistic projects have a political side”

The result is a seemingly empty, but full, building.

Exactly. There’s no room for anything else in the original pavilion because we’ve built another pavilion inside, which is why we say that the original one is full. But the other pavilion, my one, is indeed empty. It combines seemingly contradictory concepts, but that are experienced at the same time: what’s straight and what’s crooked within that architecture, there’s a space where you’re both inside and outside at the same time, we can talk about a copy and original...

And how has the general public reacted?

There’s been all sorts. It’s a project where there’s a risk that the audience walks in and out and doesn’t spend enough time inside thinking about why it seems like there’s nothing there, why this void is put forward, what happens, what’s behind this seemingly stripped-down proposal; and for them to leave with the idea that nothing’s been done. But if they spend some time inside the pavilion, if they appreciate that unusual things happen, then they come to understand the play on this twice-crooked building.

Aren’t you afraid that the audience will only see the visual aspect and won't understand the deeper underlying idea?

It’s true that one thing is your aspiration, what you put forward and what you’d like the project to convey, and another is how it’s received. But I’m not worried that people come to their own conclusions or interpret it in ways that don’t match mine. If that happens, it’s great, for the work to be able to suggest and put forward things beyond what I’d considered. That’s fantastic.

“I’m not worried that people come to their own conclusions or interpret it in ways that don’t match mine. That’s fantastic”

Does the audience need the talent of artists to make them think?

I’m not sure if they need it, but I think that we have to take advantage of art’s ability to make us reconsider certain things from a place of resistance to certain world dynamics. In the case of the pavilion, suggesting absurd architecture, but that at the same time questions and considers the idea of time, space, or how an exhibition should be visited. Art has the capacity, not to change the world, but to spread reflections and critical thinking about the reality we live in. If that helps someone to see things differently or question reality, that’s a lot.

That talent has helped you to achieve success, something elusive for many artists. What does this mean to you?

For me, it’s working on what I like: being an artist and creating my work. That’s already a success and it’s not easy. So many artists can’t do it! Furthermore, there’s no doubt that taking part in the Biennale is a privilege in the sense that the entire world of art goes through there and it gathers many people who can see your work. That can help you to be more successful. Or, on the contrary, it can also have a negative effect if a project isn’t interesting.

“Art has the capacity, not to change the world, but to spread reflections and critical thinking about the reality we live in”

And it leaves you more exposed to critics.

Indeed! I’ve seen critics of all sorts, favourable and unfavourable, but that’s inevitable. In any case, what’s important is for you to be sure and reasonably satisfied with what you’ve done, after that, what will be will be... If it’s positive, fantastic, and if it’s a well-argued and consistent negative opinion, then it’ll also be useful because it helps me reflect on and consider things that, perhaps, I haven’t taken into account.

What’ll happen when the Biennale is over, will your pavilion disappear?

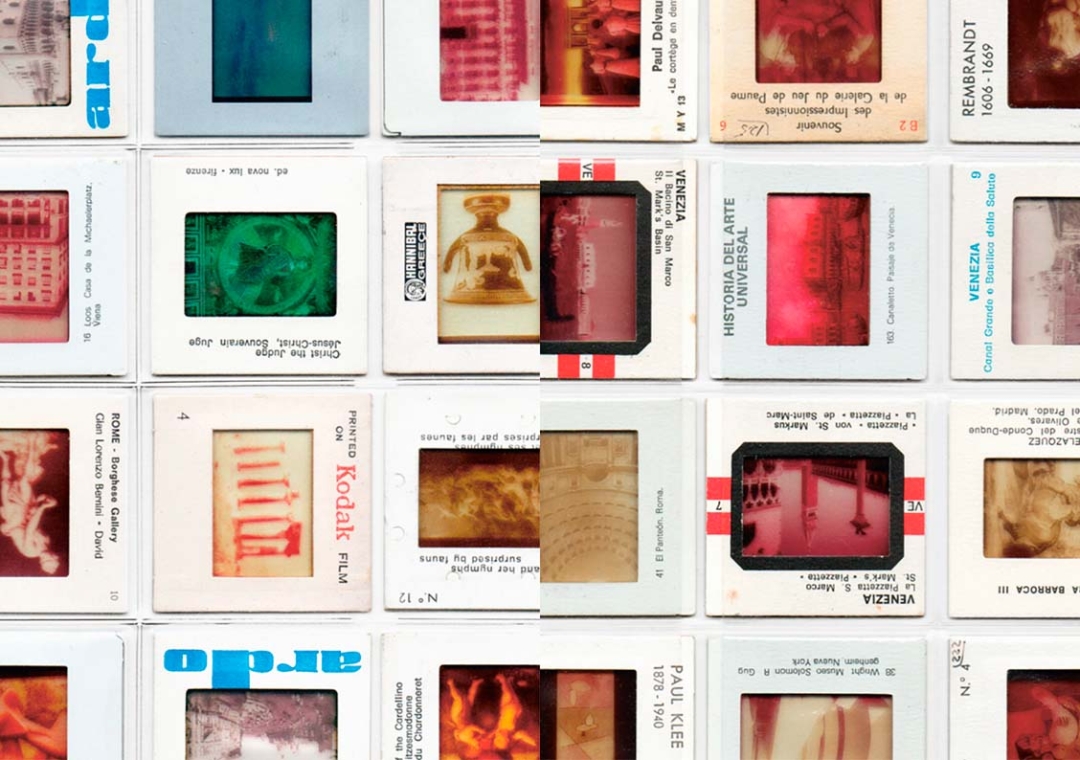

Yes. There’ll be the six artist books left that we released as a complementary project, which must be looked for in different corners of the city, but there’ll be nothing left of the pavilion. At most, a piece of plasterboard from the wall, as a keepsake, but the rest will be recycled and will disappear. In fact, this also gives it meaning: it’s a project that is so closely tied to the Biennale, that it’ll also be fleeting.

And what do those six books propose?

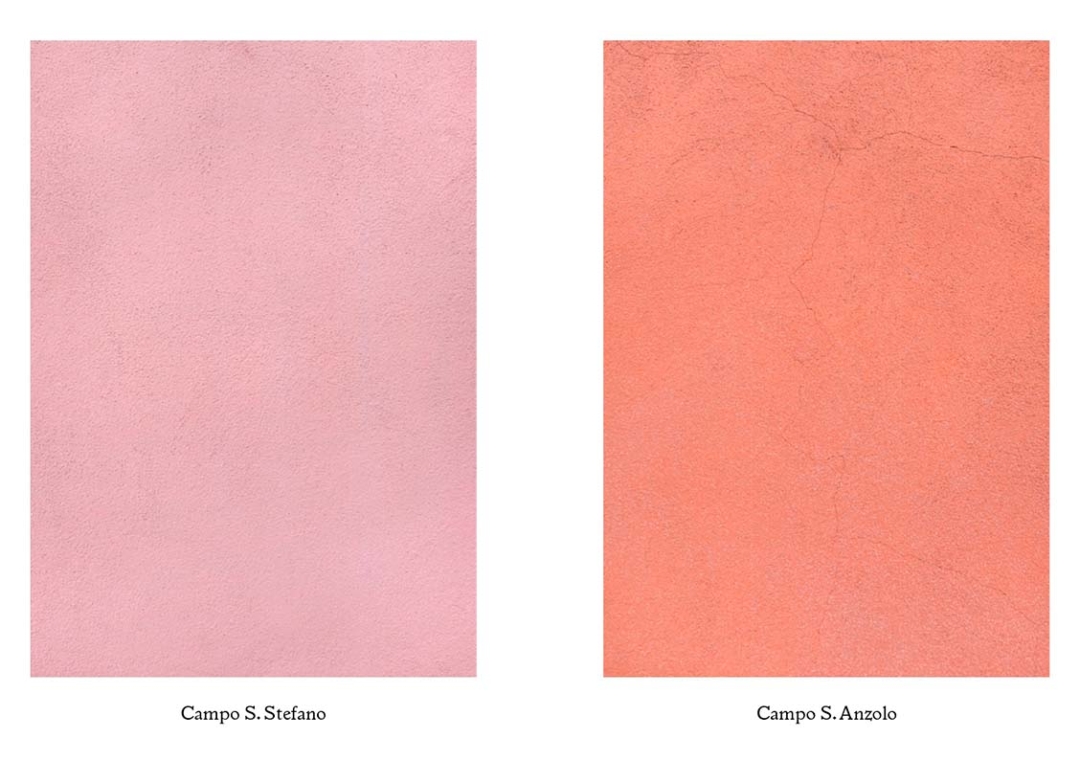

We didn’t want to limit ourselves to the building’s specific space, rather put forward a proposal that’d include Venice, making people experience an alternative to the more touristic route that they wouldn’t normally do without looking for these books. Furthermore, they also include previous works of mine that, hypothetically, could have been in the pavilion but aren’t.

‘Correction’ can be seen during the 59th edition of the Venice Biennale International Art Exhibition until the 27th of November.