María Hesse

A woman among paintbrushes

If there’s one essential in María Hesse’s life, it’s her paintbrushes (and her cats, almost as viral as their owner). Through them she adds colour, sensibility, and passion to the pages of all her books, capturing, from a female perspective, a unique universe full of conundrums and fantasy that explores both her own life and the lives of others like Marilyn Monroe, David Bowie, or Frida Kahlo.

While her classmates drew basic doodles, María Hesse (Huelva, 1982) illustrated her notebooks with elements connected to each detail that appeared in the stories told by her teacher in class. That’s how her teacher realised that that girl had the soul of an illustrator. A premonition that was only missing the level of success she’d achieve. Frida Kahlo: A Biography (Lumen), translated into 14 languages, appeared in 2016, followed by Marylin Monroe and David Bowie. Later, María told more intimate tales in Pleasure (Lumen), and last year she defended the rights of women to be how they want in Bad Women (Lumen).

The renowned publisher Taschen included her in their list of the 100 best illustrators in the world. Success that, thankfully, doesn’t overshadow how naturally and serenely she manages her profession-vocation. We chat to her while her cats Patti (after singer Patti Smith) and Leonora (after painter Leonora Carrington) stroll among paintbrushes and paints to the delight (and patience) of the illustrator whom, nevertheless, looks at them with the graciousness of unconditional love. “I’ll say that we have to be careful with how we name our pets, because the first one is a punk and the second, a British lady, all she’s missing is her teacup,” she laughs about her felines.

It’s only been ten years since you trained as an illustrator, do you think you’ve had a lot of success in a short period of time?

It hasn’t been that short or, in other words, a lot of things have happened in this time and recognition has been gradual. It doesn’t come overnight. Before publishing the Frida Kahlo biography, I’d already done thousands of things. I started out doing primary school textbooks, for example, which is a job many illustrators do and that, although less visible, is equally valuable. I also did custom portrait commissions and opened my online shop. There’s a lot of work behind my current visibility.

“Recognition adds value to your work, but for me it’s much more important that a reader tells me that my work moved them”

Did your talent for drawing come late in life?

Not at all. I’ve always known this is what I wanted to do. What happened was that I wasn’t able to do Fine Arts, so I signed up to Teaching. When I was preparing for the public examination, I realised that I wasn’t happy and decided to change course: “I won’t wait to pass the public examination, I’ll try to be an illustrator,” I told myself. And that’s what I did.

It’s hard for Spanish talent to be recognised abroad. This isn’t your case. How do you take the recognition by Taschen?

I don’t even think about it. Obviously, this kind of recognition adds value to your work and helps, but I don’t really care about rankings. For me it’s much more important that one of my readers tells me that my work moved them. That’s a beautiful and powerful feeling indeed.

Your work has been defined as feminist, how true is this?

I’m a woman and I’m a feminist, I can’t deny that a big part of my work follows this discourse. There’s a fight for recognition behind Pleasure or Bad Women, for example, but my work doesn’t always follow that narrative. In fact, I’m kind of annoyed at having to talk so much about feminism instead of my work processes in interviews.

Let’s talk about work then, how much symbolism is behind your drawings?

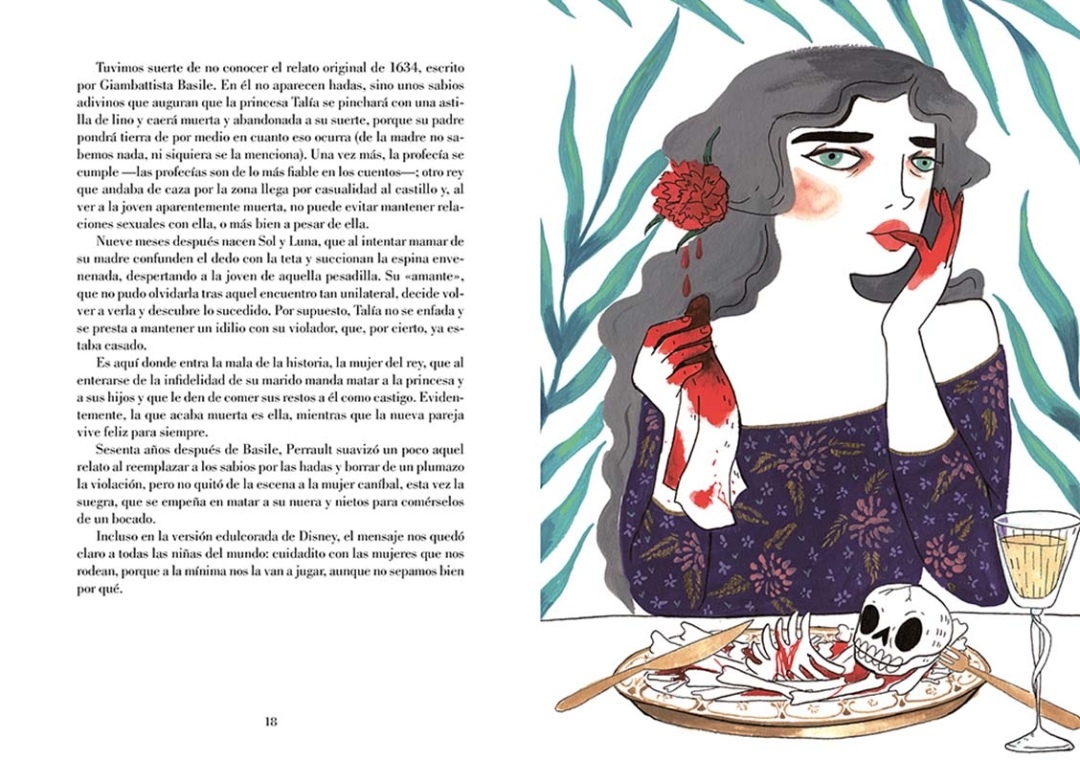

A lot, and it changes from book to book. Even the colour range changes, because I think in a very visual way and am moved by feelings. For example, in Bad Women I play with flowers and according to the women I present, I use one or another: some represent magic and witchcraft, others, tragedy. Previously, I’d used branches and leaves: in Marilyn: A Biography blue branches were related to sadness. But animals are also symbols. However, I’d rather not explain their meaning because I’d rather the reader interpret them in their own way and make the illustration their own. That’s where my work takes on the most meaning.

¿Why Frida, Marilyn and all those Bad Women and not others? Do they have anything in common with you?

They’re women I’m interested in for a variety of reasons. Perhaps Marilyn connects me to vulnerability, and Frida, to vitality. But it’s extremely hard to define that connection because when you choose a character, you don’t even think about what you have in common. You do it because they have something that interests you and to a certain extent it’s an opportunity to be her for the time, you’re making the book. At least, that’s how I experience it, intensely.

“More than fear of losing visibility or recognition, which isn’t something I need, it’s fear of not working as an illustrator”

In your latest book, Bad Women, you’ve included an extremely personal introduction encouraging every woman to be how they like without being labelled for it. Was it therapeutic?

All books are. The more personal they are, the more therapeutic. I’d say that Pleasure was more so than Bad Women because it’s a lot more about me and the moment you start to delve into yourself you experience greater healing. It’s a book about how to experience sexuality and writing and illustrating it helped me to be more authentic and honest with myself. Oftentimes, women do things because that’s what we’ve been taught is normal, and that’s how you experience it and take it in, until you suddenly understand that that’s not the case and you find your place.

Are you afraid of your illustration style going out of fashion?

It’s not a paralysing fear, but sometimes it’s there; to say otherwise would be a lie. Although more than fear of losing visibility or recognition, which isn’t something I need, it’s fear of not working as an illustrator. However, there are lots of ways to do it and, one way or another, I know I’ll carry on drawing and telling my stories, even if only a few people read them.

Can you tell us about your next project?

No (laughs). Well, alright then, my next project will be the TANTANFAN diary about recipes from films. It’ll be out in June. Regarding my next book, all I can say is that it has nothing to do with my previous work. It won’t be an essay or follow a feminist theme. It’s time for me to take a little break from my campaigning stance.