Joana Biarnés

When Photojournalism Conquered Fashion

Joana Biarnés was Spain’s first woman photojournalist, one that turned a man’s trade upside down with her extraordinary eye and journalistic pulse. Until 22 December, the Centro de Arte de Tarragona, in partnership with the Photographic Social Vision Foundation, will hold the exhibition 'Joana Biarnés, street fashion', showcasing 88 unpublished images that provide a snapshot of Spanish fashion and society from the 60s and 70s.

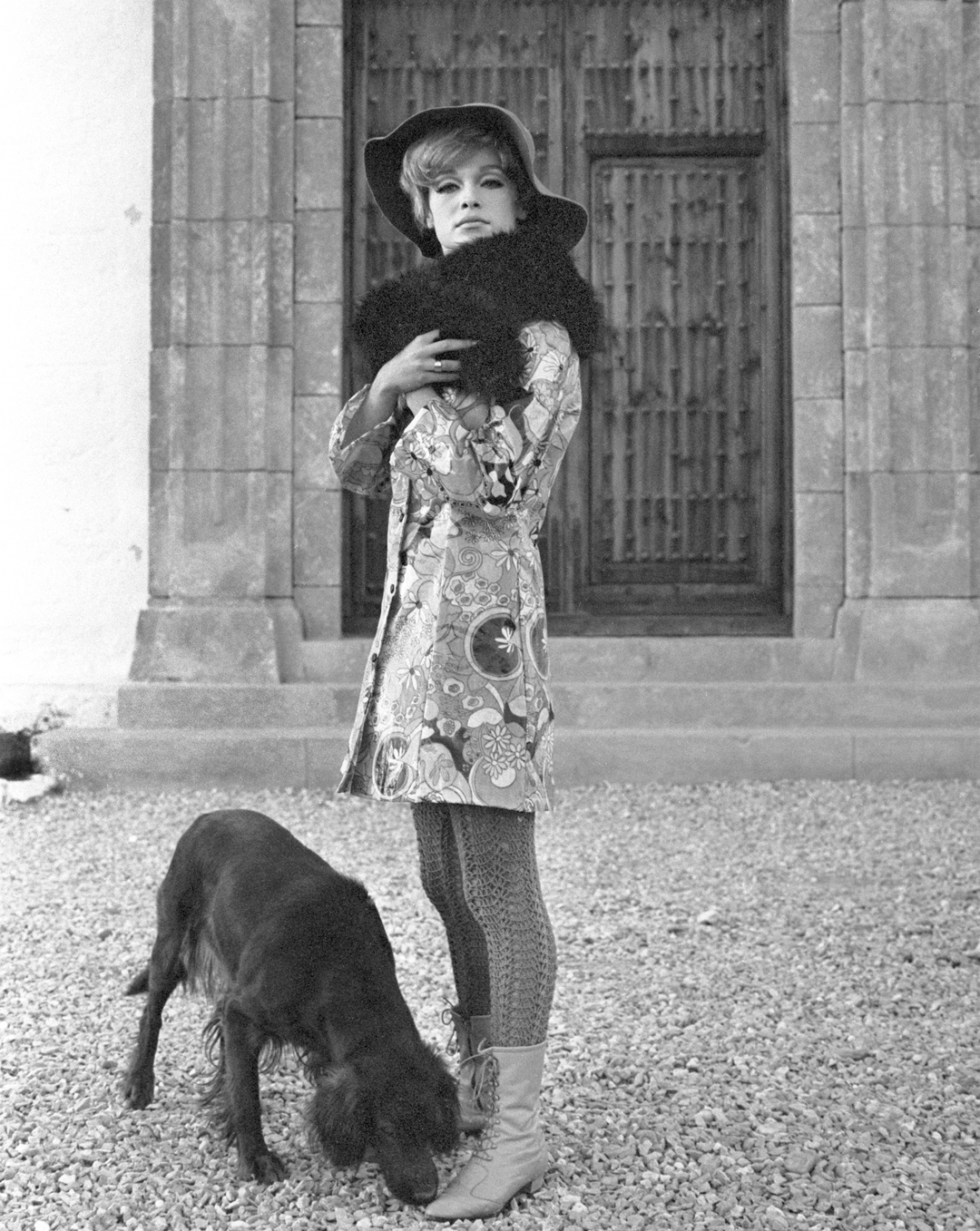

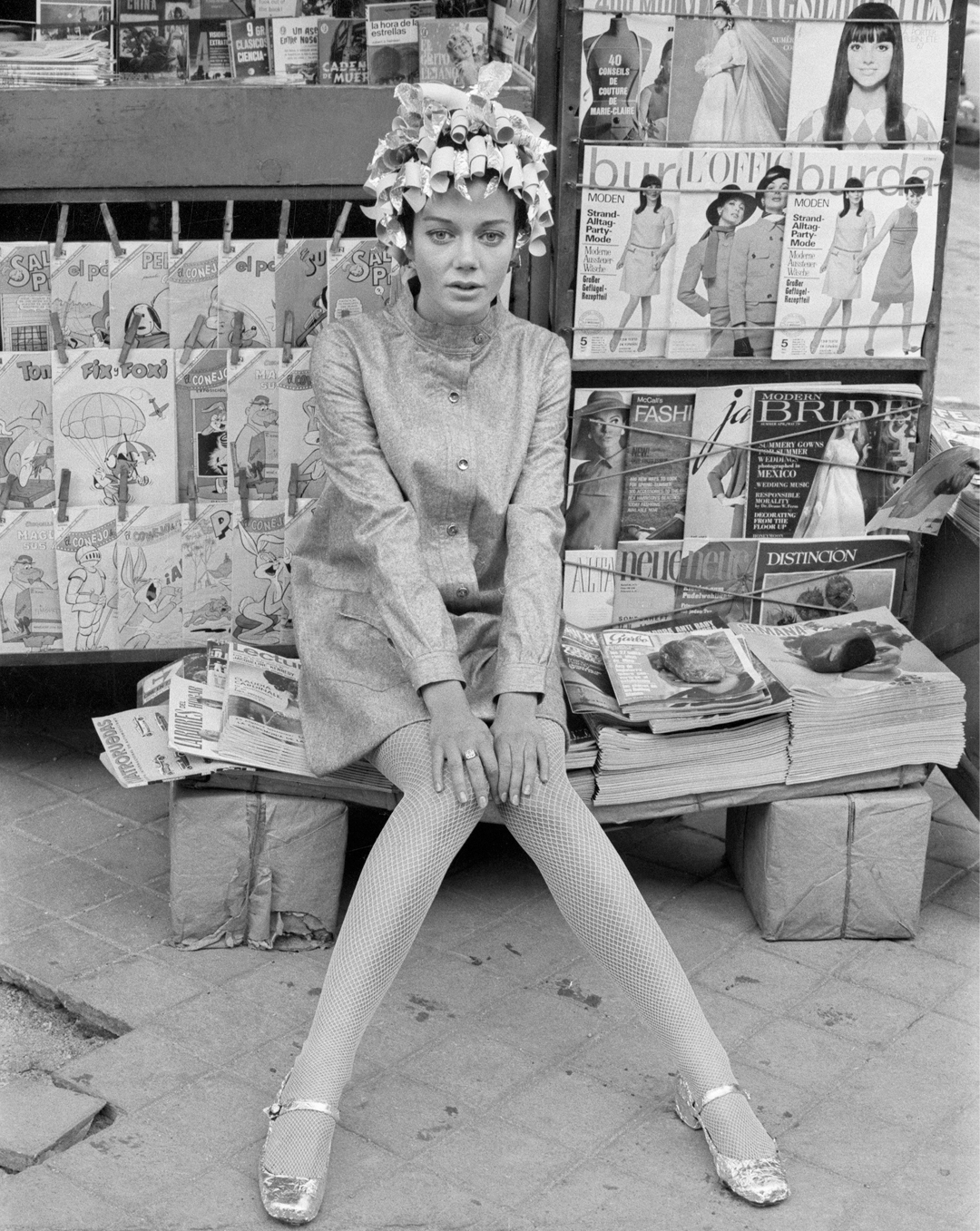

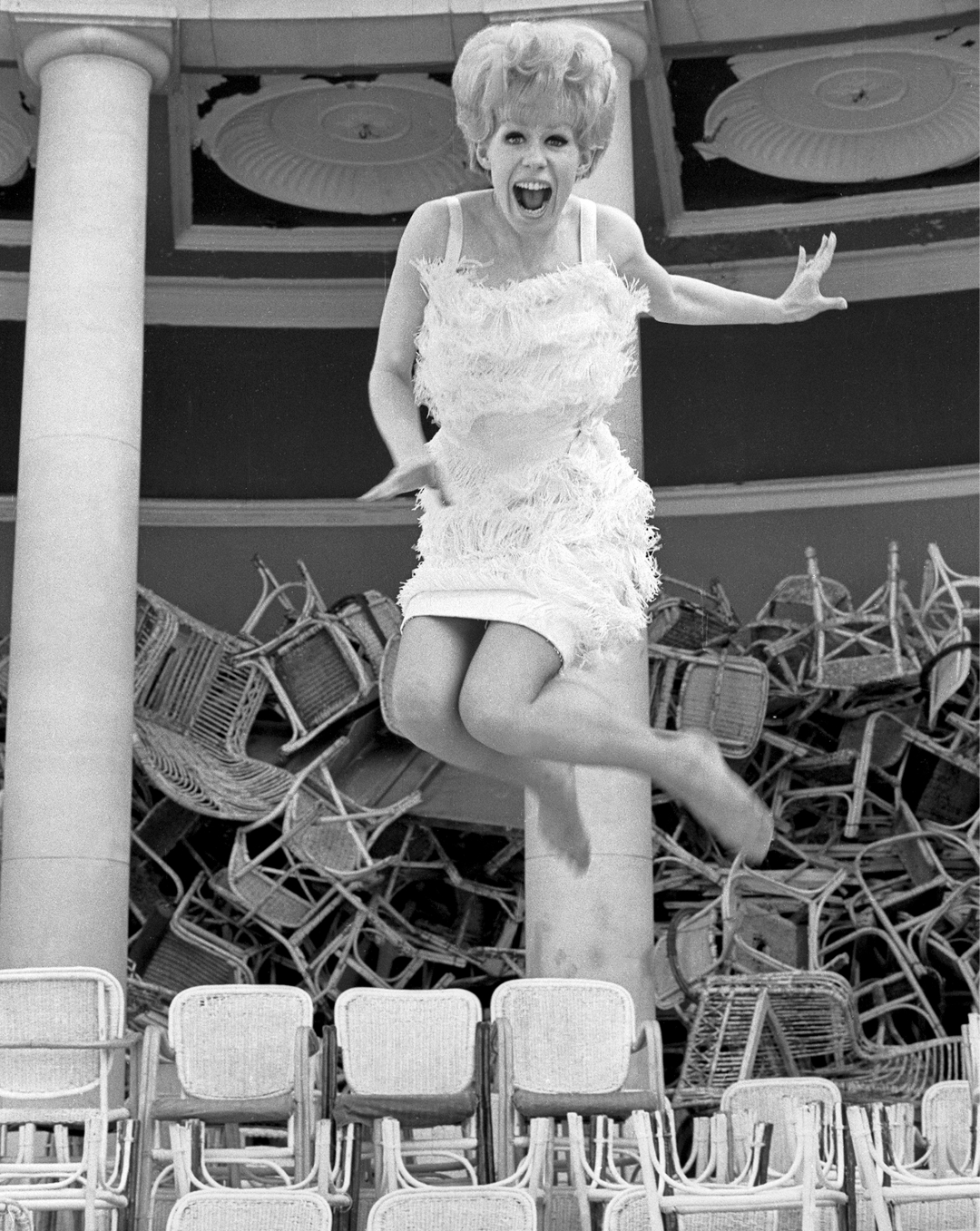

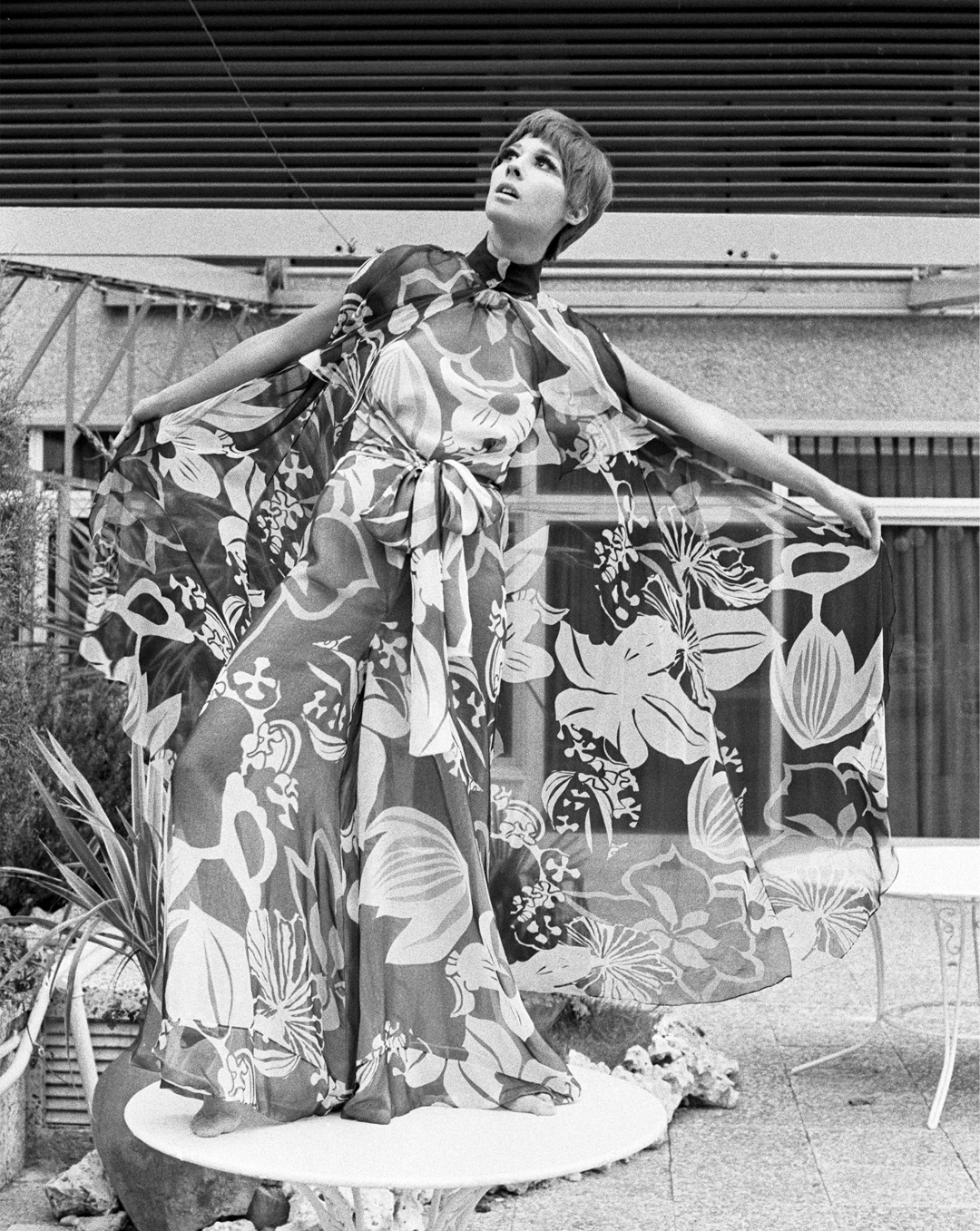

Seven models wearing scandalous mini shorts and high boots jump like superheroines against a crane tower at the M30, in the outskirts of Madrid. We hear the click of a camera. Model Rosanna Yanni poses wearing psychedelic op art makeup, under the dumbfounded gaze of a woman in Madrid’s El Rastro. Click. A model with a Rapel hairstyle—a popular hairdresser in the 60s—sits awkwardly on a pile of magazines in a newsstand. We can imagine her asking: “Here, really?", “Yes, look at the camera.” Click.

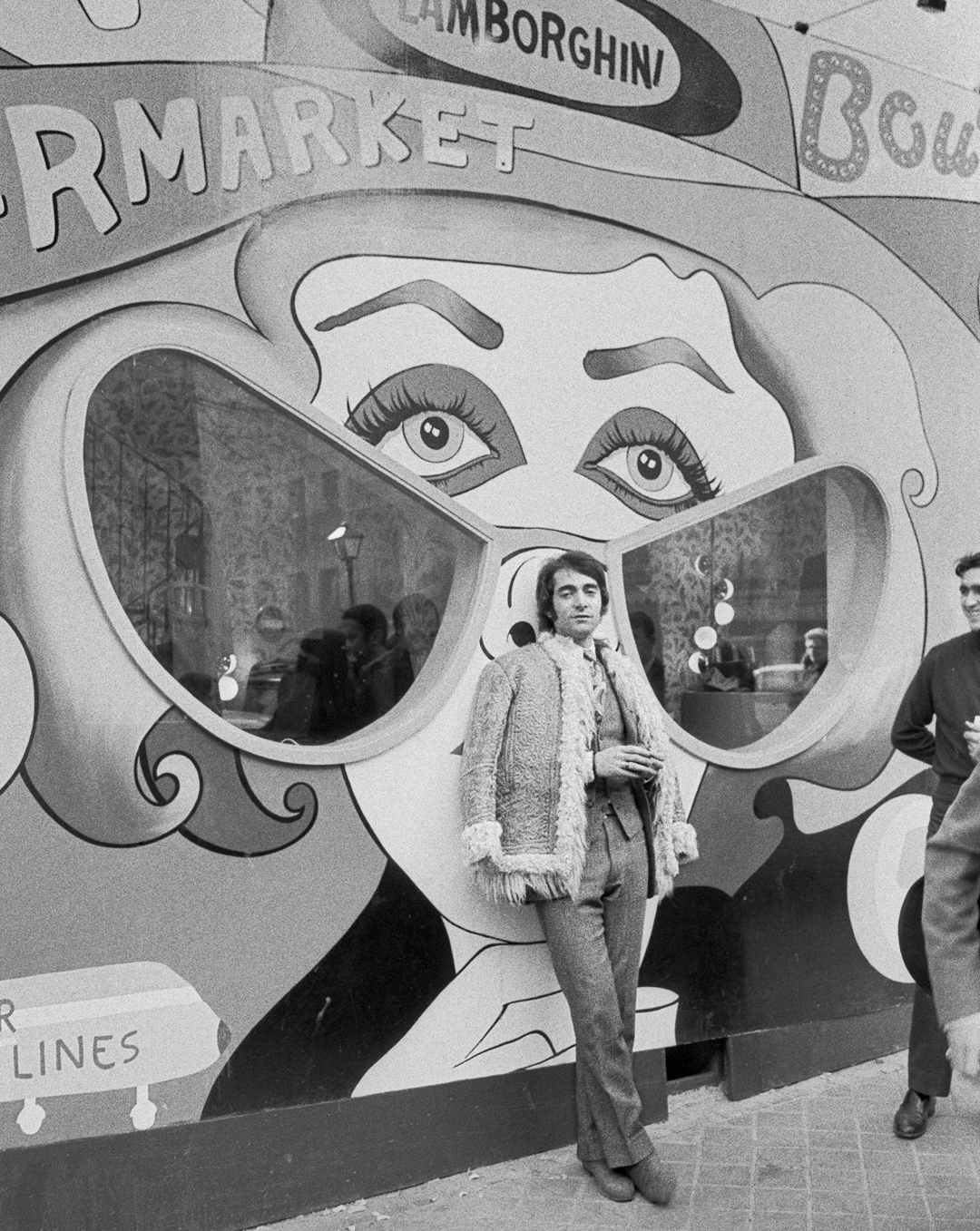

“Joana would tell me: ‘It was fun today. I took Marisol to this place to shoot some photos and she kept asking me: ‘Weren’t we supposed to go to the studio?’” Joana liked being on the street a lot because, being a journalist, that’s where she got most of her news,” Jean Michel Bamberger, her widower, recalls. True to her photojournalist origins, whenever she made editorials for the daily Pueblo or the Moda en España magazine, Joana Biarnés (Terrasa, 1935-2018) turned her models into the leading characters of street micro-stories. In the 60s, in the United States and in France, fashion photography was affected and sophisticated, but in Spain Biarnés did the opposite: her photos followed the path Richard Avedon had taken for Christian Dior in the 40s, with models posing on post-war Parisian streets.

Massiel's Dress

“Joana took the immediacy of photojournalism, where there is no staging, to fashion. Unaffectedness was her hallmark, which makes her photos easily identifiable. And it was precisely that freshness that made her treat the models and designers she portrayed in a more casual way. She was also a very fashionable woman, always up to date with international trends; she used to spend a lot of money on foreign magazines... She could have been a model herself if roles had been switched”, says Josep Casamartina and Parassols, the exhibition’s curator. “Her first jobs were fashion edits for Asunción Bastida, but she wouldn’t set up the session in the studio but take the models down to the street to do the shooting there. In the 50s, photographer Oriol Maspons had already taken fashion photography to the streets, but he could photograph models wearing couture dresses in the slums. Joana didn't even consider it. She wasn't interested in making that contrast because it was naturalness what she was after.”

Among the 88 images on show, a particular story stands out: the adventure to buy the dress Massiel wore at the 1968 Eurovision Festival, which she won. Joana Biarnés was the singer's personal friend and travelled with her to Paris to choose a dress after not finding one that would convince her at Marbel Junior's showroom.

Massiel had Dior in mind, but, like in the legendary Pretty Woman scene, they didn’t offer her a single dress. “From Dior we went to Salon du Prêt-à-Porter to see the work of Moda del Sol, pioneers of Spanish haute couture, with José María Fillol, Nacho Ruiz and Miguel Marinero. The initial idea was to wear a dress by a Spanish firm, but they end up trying on dresses by French designer André Courrèges,” the curator says. “There are very funny pictures, like one in which she’s wearing a rather cheeky see-through dress adorned with geometric shapes on the hips and the chest. Joana Biarnés took that photo with a mischievous yet respectful eye, placing Massiel in front of a window so that the transparency can only be intuited. But it isn’t the eye of a man, who would have tried to possess or dominate her. Joana's way of photographing, embodied in the image of the models with the crane tower in the background, radiant and powerful women, was a song to freedom and says a lot about her feminine and feminist vision.” It was finally the Courrèges dress that they chose for Eurovision, which was much more discreet, flared, white with blurry pink flowers, one that would become the most coveted and copied garment that year.

“Joana's way of photographing was a song to freedom and says a lot about her feminine and feminist vision”

The exhibition Joana Biarnés, moda a pie de calle was one of the last projects she was involved in. She retained in her memory, and in her retina, every photo of public figures: Karina, Tita Cervera and Marisol, was well as designers such as Cristóbal Balenciaga, Mary Quant, Juan Rocafort, Antonio Nieto and Elio Berhanyer. Biarnés' work stands out for the spontaneity of her fashion edits and the fine irony of the social portraits showcased in this exhibition, with models clad in fur holding hunting shotguns, fun private shows for the aristocracy, showrooms for ladies with their children sitting at the runway, and beauty pageants such as La Guapa de Madrid con Gafas, in which the winner was left without a dancing partner. “We reviewed more than 3,500 negatives, of which we picked 88. She was so excited about this project... But we lost her, all of a sudden. I know Joana would have loved to see this exhibition, a snapshot of an era but also a tribute to her work and freshness as hallmarks of photojournalism turned into fashion photography,” Casamartina i Parassols concludes.