Since opening on the 17th of April, Espacio Iberia has welcomed dozens of guests with one thing in common: their infinite talent. Talent that has inspired all the people who have sat there to listen to them.

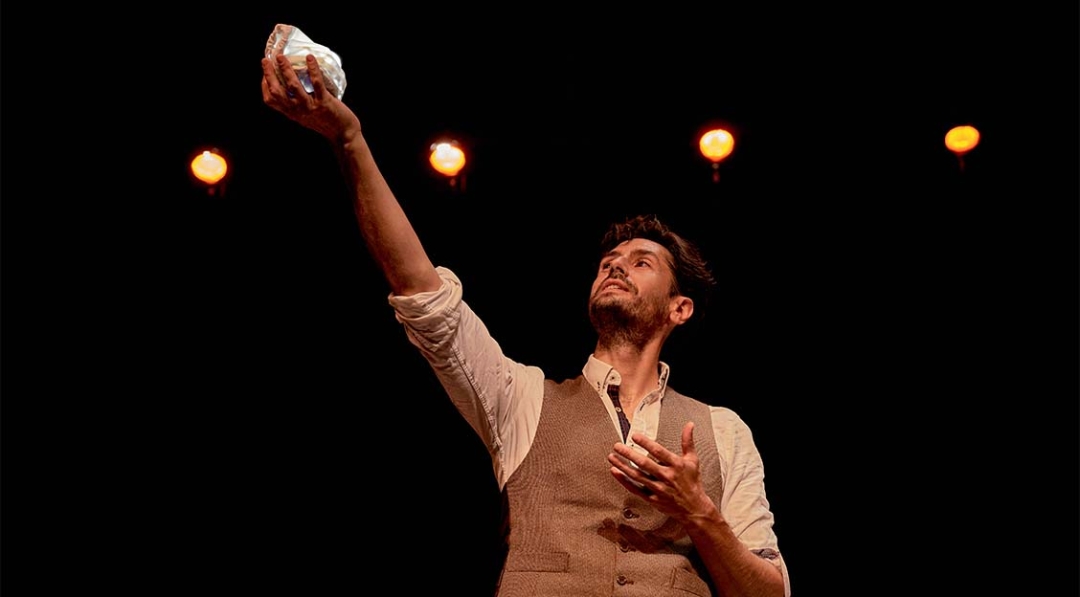

Each person has their own place in this world, and Sergio Peris-Mencheta’s is the theatre. As stage director and producer (Barco Pirata), this stage activist seeks to share his passion and captivate new audiences. Risk, commitment, and emotion are the distinguishing traits of his plays, including the latest: 'Una noche sin luna', nominated to four Max Awards, 'Ladies Football Club' and 'Castelvines & Monteses'.

Sergio Peris-Mencheta (1975) rose to fame exactly 25 years ago with the series Al salir de clase. Today, after a film career that has led him to rub shoulders with international stars such as Sylvester Stallone or Helen Mirren, he’s one of the biggest theatre directors in Spain. In fact, he talks to us a few days before the gala of the Max Awards, where he’s a firm favourite, together with inseparable Juan Diego Botto, with the play Una noche sin luna. If they win with this moving journey through the life of Federico García Lorca, they’d reap the same success as with Un trozo invisible de este mundo in the 2014 edition.

After 25 diverse years working equally in film, theatre, and television, which do you love more?

They’re different loves. As an actor, I feel freer onstage, although I must admit that for some time, I’ve also had more creative freedom in audiovisual formats. I guess growing older has granted me the respect that I was lacking at the beginning, and now I feel more heard as an actor.

Despite your greatest achievements coming from theatre, the general public knows you more for your roles in films and series. Is this somewhat infuriating?

Not at all. I love being able to do both things and that they both still challenge me. Anger is for angry people. I’m happy directing and acting: the first allows me to live, and the second feeds me.

In fact, your career started with a surge in popularity (Al salir de clase). From the outside, it seems like you don’t miss it, am I right?

Yes. I don’t have the public figure profile. I don’t like parties or premieres. Or photos, features, promotions... I’ve managed to make a living out of a profession I love without having to pay that price.

“I’m happy directing and acting: the first allows me to live, and the second feeds me”

But before film or TV, theatre was always there. Where does your passion for the stage and acting come from?

At school I was always the class clown. I had a teacher who gave me an hour at the end of the school year to play a scene from Don Juan by Tirso de Molina with a classmate, who was also quite a rascal, and that’s where I connected to my ability. Later, at University Carlos III I discovered theatre as a profession through Inés París and that’s where I connected with that possibility.

In 2011, alongside other colleagues, you founded the theatre production company Barco Pirata, which features committed theatre, what does that “commitment” mean to you?

Theatre always involves a commitment. Unlike other artistic disciplines, it’s impermanent, you can’t keep it. Its essence is in the here and now, and that’s what it’s about even when it doesn’t try. Also, everyone who works in theatre does it out of passion, never out of vanity. No theatre actress or actor has gone down in history, unlike those in film or TV. We can hear about Rodero or Bódalo, but we only identify them because of their work in film, which is scarce compared to what they did onstage. Doing theatre is activism. Theatre is born and dies every day and dedicating your life to it is a way of understanding life and, therefore, death.

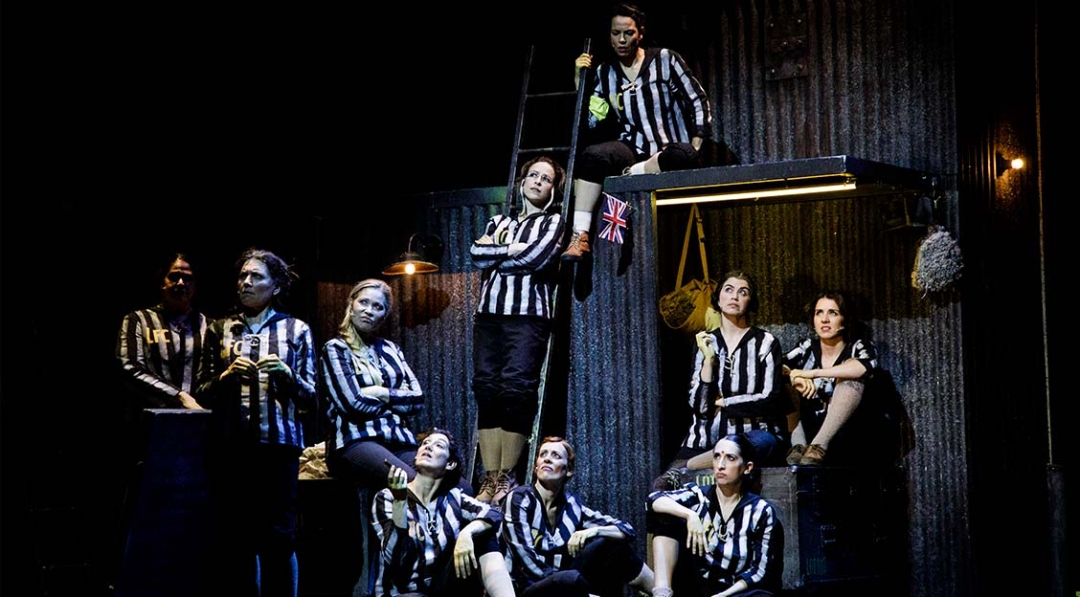

And speaking of commitment, the women featured in your latest release (Ladies Football Club) know quite a lot about that, right?

Like all plays, Ladies Football Club is about us. It’s a homage to our grandmothers, mothers, daughters... Despite the improvement, it reminds us of all the work that still has to be done in terms of gender. Personally, it has shown me that, despite claiming to be a feminist in theory, within me is an unbearable condescending misogynist afraid of everything feminine. Dealing with this has been, is, and will be the work of a lifetime, I’m afraid.

In 2014 you succeeded, alongside Juan Diego Botto, at the Max Awards with Un trozo invisible de este mundo, something that could happen again this year with Una noche sin luna. What do you each bring to the other to conceive two such superb plays?

We’re two friends who found each other through theatre. Two friends of the same age that, despite being really different, share a similar emotional, mental, and cultural paradise. We understand art and theatre as a mirror and a way to heal ourselves and the world.

The main (and only) character of Una noche sin luna is Federico García Lorca, do we need to reclaim his figure now more than ever?

Federico is eternal, like his work: his poetry, his theatre, his illustrations, his conferences... Looking at yourself through Lorca is giving yourself the opportunity to rediscover yourself as an artist but, above all, as a human being.

The pandemic hasn’t done cinemas much good, do you think theatre will withstand the blow better?

Theatre, like Lorca, is eternal. A ritual that, once you’ve experienced successfully —seeing a performance that moves you— it’s hard to not get hooked. Live art, here and now, with all its humanity and fragility. Sharing time and space with a crowd of strangers that stop their lives for an instant to, curiously, observe life.

“Looking at yourself through Lorca is giving yourself the opportunity to rediscover yourself as an artist but, above all, as a human being”

Attracting young people to theatre was one of your goals with Castelvines & Monteses, another of your latest plays. What a challenge!

A challenge we passed with flying colours. Our fundamental purpose at Barco Pirata is to create audiences, and that’s why we’re obsessed with captivating youngsters. And that means, among other things, facing impossible challenges like Castelvines & Monteses, a Lope de Vega with live music.

Throughout your career you’ve been fortunate to work with great actors and actresses in Spain, the United States, Mexico, France... Who dazzled you with their talent?

I’ve never worked as an actor with Juan Diego Botto, but as a director I’ve seen him work in many plays and he’s probably the actor I admire the most today. As for actresses, I greatly admire María Isasi, Marta Aledo, Marta Solaz, each and every one of my ladies and my castelvinas... And I have an unforgettable memory of Laia Costa, who seems wild to me.

On the topic of talent, how would you define it?

First, I know it’s not a prerequisite to being successful. There are other factors, like fortune, which end up being more decisive, especially professionally. And I like talking about talents in plural. Finding out what your talents are is the work of a lifetime. If I had to wish for something for myself and my children, it’d be to learn to accept what comes and what is without judging it as good or bad. And being at peace with oneself, without fighting expectations. Perhaps this way it’s easier for talents to flourish.