El Roto

Following Goya’s Footsteps

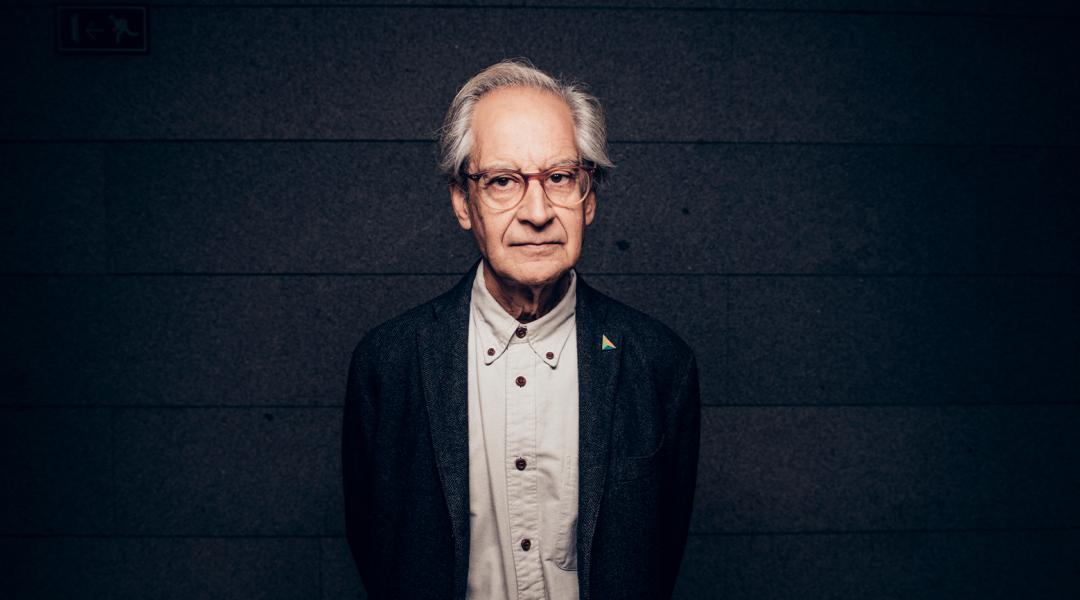

Andrés Rábago wanders around discretely hidden behind the pseudonym El Roto: for many, the most clearheaded portrait painter in current society. Today, the illustrator is featured in the Museo Nacional del Prado with ‘One Cannot Watch’: a splendid exhibition inspired by the illustrations of Francisco de Goya.

When Andrés Rábago (Madrid, 1947) was young, he used to visit the Museo del Prado with his father and brother some Sundays before going to play at the Parque del Retiro. Among all the rooms he walked through, the one dedicated to Goya was always one of his favourites. What that boy didn’t know was that, on the art gallery’s 200th anniversary, he’d see his illustrations exhibited not far from those of the genius artist from Aragón.

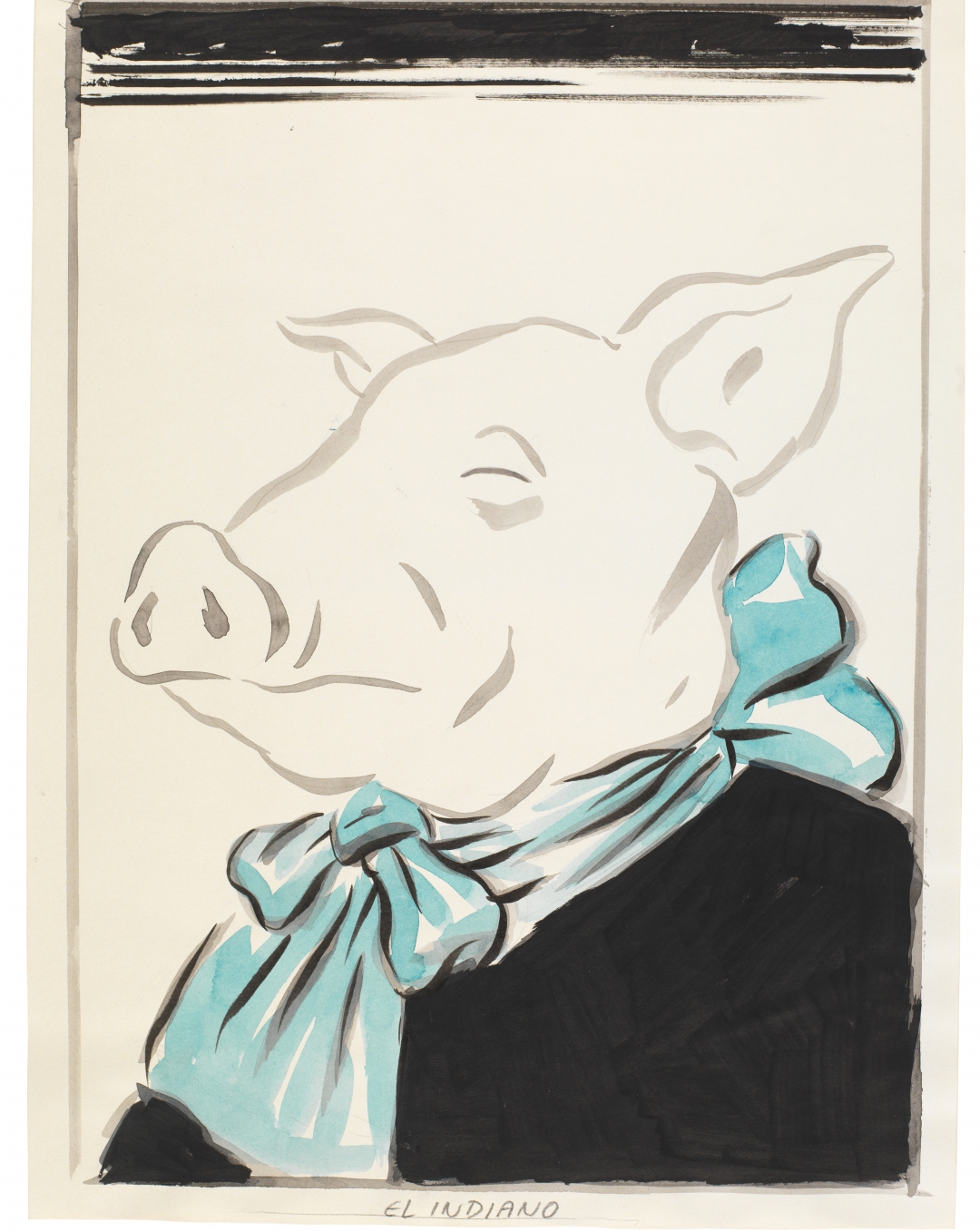

The El Roto. One Cannot Watch exhibition, curated by José Manuel Matilla (the museum’s head of Illustration and Print Conservation) and housed in the Jerónimos Cloister of the Museo Nacional del Prado (until February 16), consists of 36 pieces that, according to the commissioner, “are 36 punches, like the 320 drawings by Goya exhibited in the room above. Like these, El Roto’s illustrations invite us to reflect”. It was precisely Matilla who, twenty years ago, suggested to Rábago to take inspiration from the Aragonese artist; a dream which has finally come true. I haven’t been lucky enough to live alongside Francisco de Goya, but I have with Andrés Rábago, an artist that shares part of the critical essences that are within Goya’s work. Somehow, I feel closer to Goya after spending time close to Rábago in the last few months”, admits Matilla. El Roto receives praise with satisfaction; but also, with the absolute humility that is so typical of him.

How did this adventure come about?

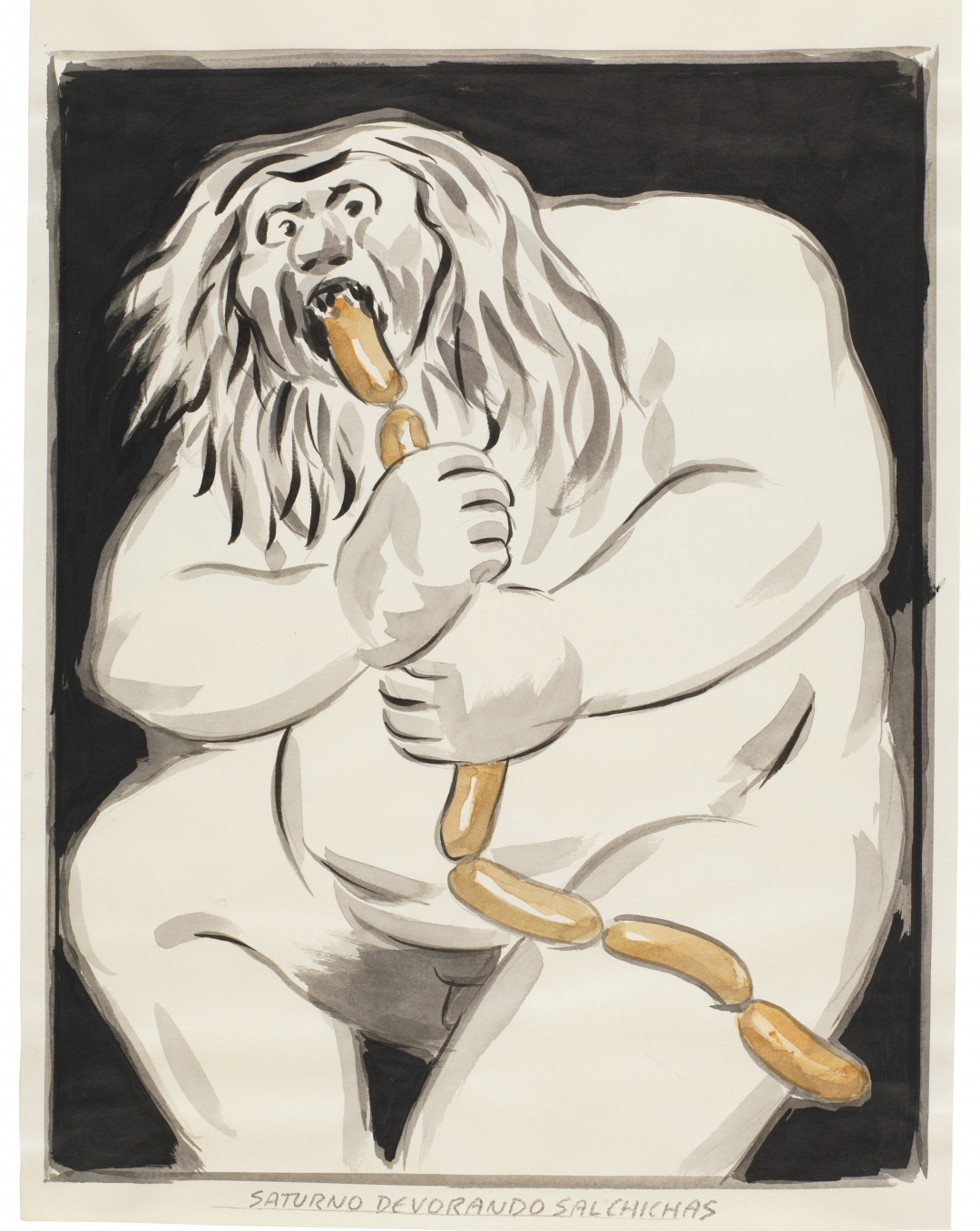

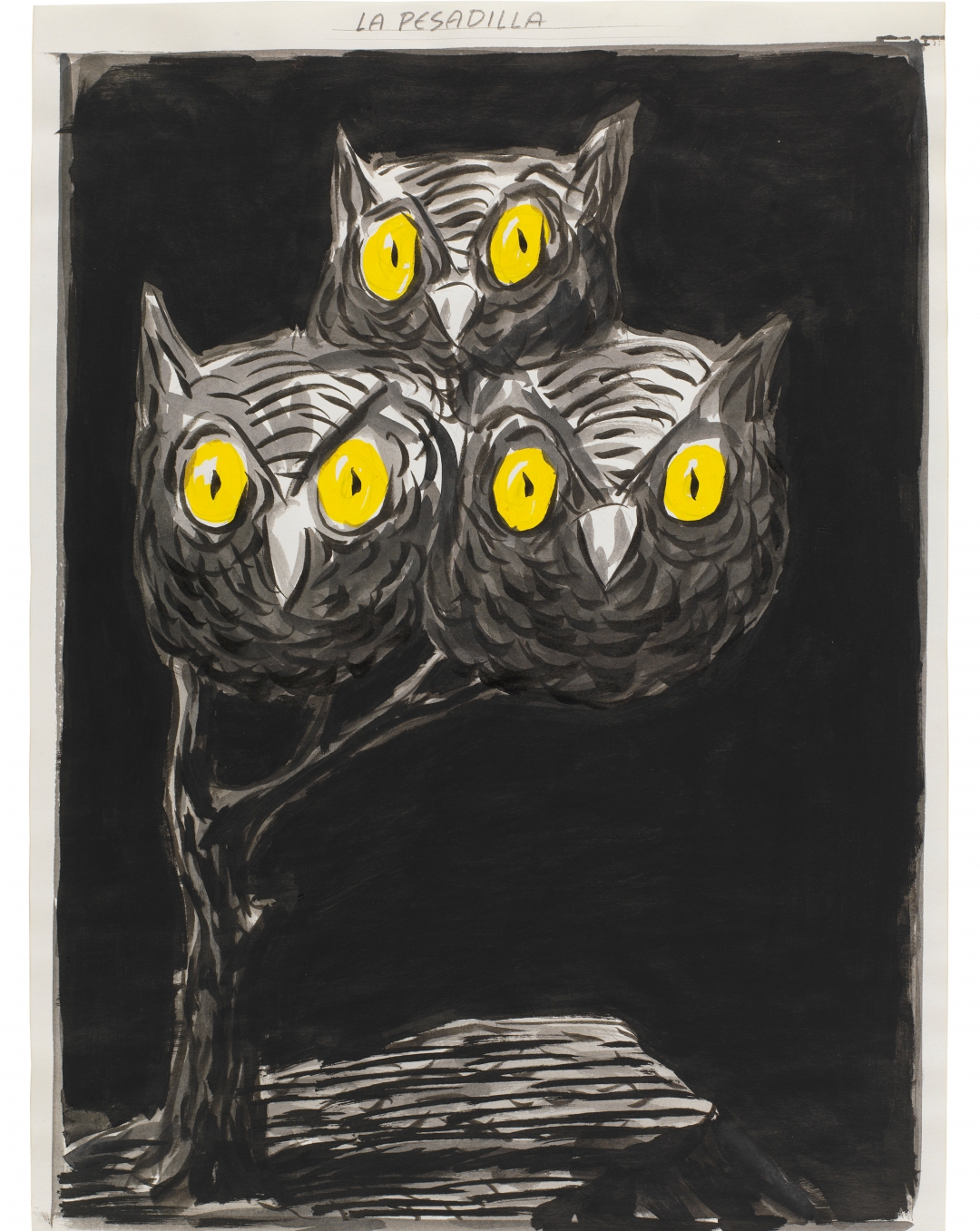

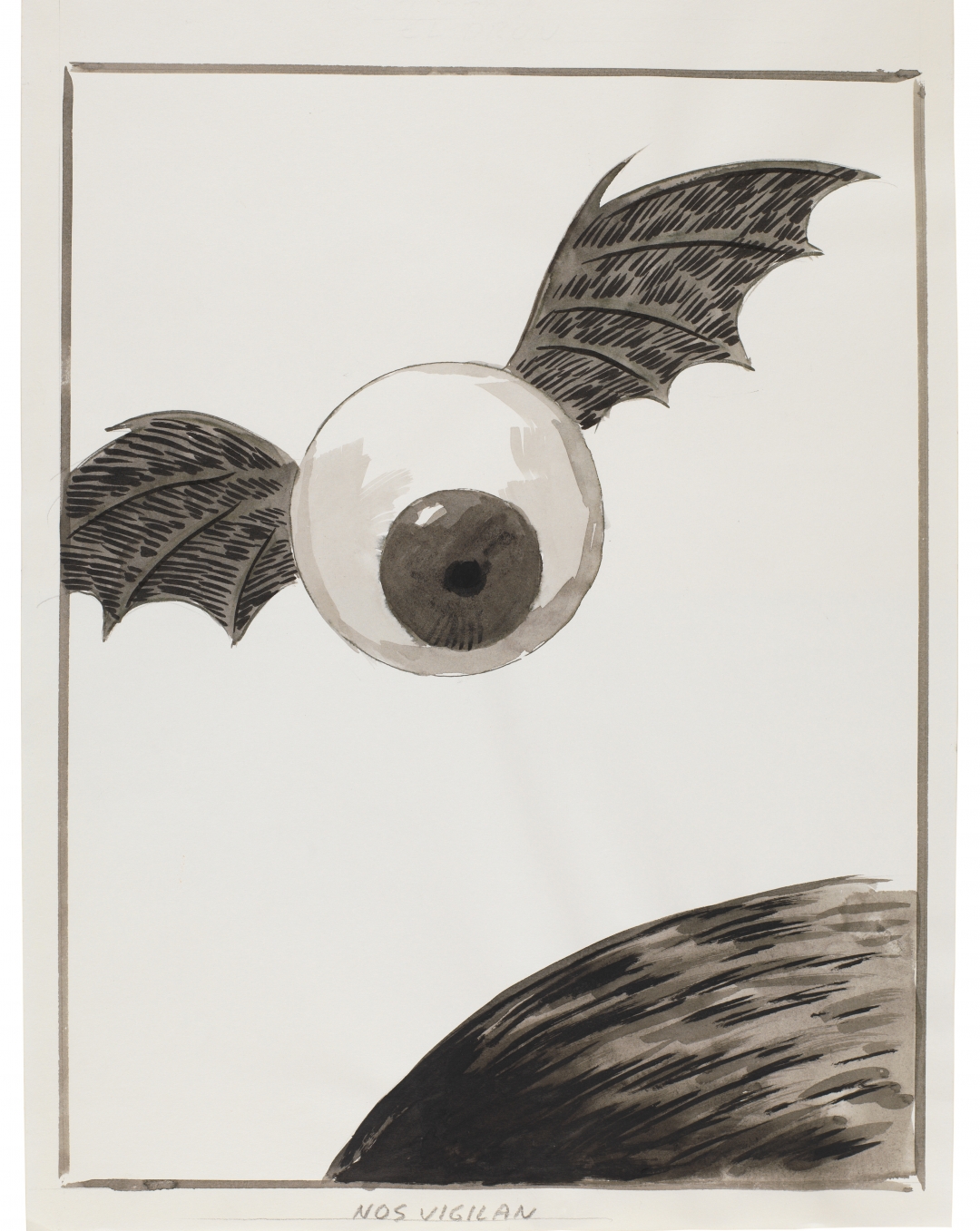

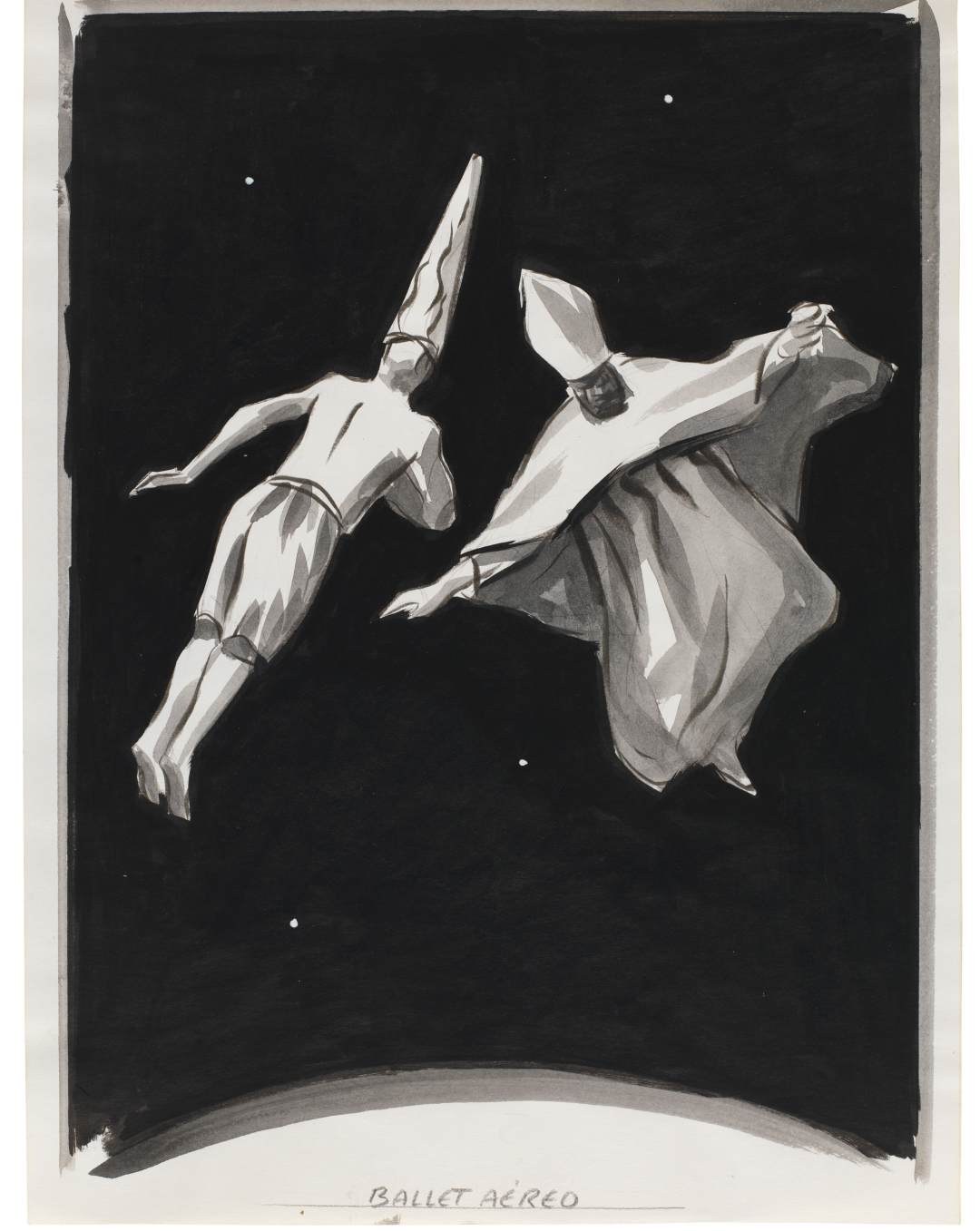

I had forgotten that conversation I had about this with José Manuel Matilla twenty years ago. But I’m not surprised that it’s taken me this long to decide to tackle this work. When someone suggests a topic, I struggle to work on it because, if it’s not my idea, it always takes me time to make a decision. In this case, perhaps I’ve taken too long, but for me it’s been worth waiting until I had matured to tackle work such as Goya’s, which isn’t at all simple. I've tried to use some elements in his iconography, which is part of the DNA of anyone with a cultural interest in our art. I’ve also used some favourite topics, trying to also reflect his view of what’s happening now. There are elements of his and others which belong more to me because of my personal worries, but I think that a significant part of what he addresses is within these illustrations and in the fifteen that are added to the exhibition catalogue, edited by Reservoir Books.

But why did you choose Goya?

When El Prado asked me to do something for their 200th anniversary, I walked through their rooms to see what works could contain a satirical and comical component within classical painting. I would come every Wednesday with my notebook to take notes. But the material I collected was too diverse. In the end, walking through Goya’s rooms, I realised how close I still felt to this great artist. The truth is that it’s been a very enriching project: I’ve learnt much more about Goya than I knew before, even from a technical point of view, with findings that I’ll include in my press work now.

How do you conceive this exhibition then?

This is only a fragment of how Goya’s enormous talent is still current and ours. My exhibition only pays homage to an artist that was working until the end of his life, as I hope to do, with that intensity and humanity that was typical of him. I’m only the scribe of what needs to be said. When I contemplated Goya’s work, I saw things that wanted to be told: so, the only thing I’ve done is transfer them to paper.

“When critiquing, the only limit we should admit is rudeness”

You've defined Goya as “an admirable and generous researcher of the soul”. Are you aware that that’s also what you are for many people? There are many Spaniards that, when they get up and open El País, the first thing they look for is your comic strip?

If I can be by someone’s side during their journey around the world and at this time, it gives me huge satisfaction. But the truth is that I’m not very aware of this. Yes, I guess it happens, but I’m not really worried about it when I’m working. I’m simply a witness, like Goya, of a time and a way of seeing the world. This is my job, my responsibility. The rest is beyond me.

Walking around the exhibition, we see that your vision is as true as Goya’s. Several centuries have gone by, but things have hardly changed. The human soul hasn’t changed...

Yes, for consciousness to evolve, time is very slow. Two hundred years for how we perceive things is nothing. Our vision is probably very similar to Goya’s. Many of the issues he focussed on are still prevalent today. Changes have been superficial; deep down, we’re still worried about the same problems that he addressed in his work.

El Roto during the press conference for his exhibition ‘One Cannot Watch’ at Museo del Prado. © Alfredo Arias

You used the pseudonym OPS before the arrival of democracy. Then, you became El Roto. How does Andrés Rábago get along with him?

They’re two levels of reality, or perhaps different perceptions of reality. El Roto is focussed on the surface, on the most external appearance of things, while Rábago tries to look into the depths of the soul. The first belongs to the spirit, to what’s sacred; the second belongs more to the social and political aspects of what is most immediately obvious.

Is that also the difference between your facet as a painter and your facet as an illustrator that analyses society?

I believe so, this variation happens in both cases. Even from the plastic point of view: while El Roto is synthetic and does not use colour, Rábago does, as well as moving around a more complex and emotional playing field.

Your critiques are real curve balls but, where’s the limit for you?

When critiquing, the only limit we should admit is rudeness: saying things without unnecessary aggressiveness, leaving proof of what we think, but politely.

In this tumultuous world we live in, can we be optimistic and believe that human beings can understand each other?

I think we’re obliged to be optimistic, but we also must be aware of where we are and of the dangers of the time and place that we move around in. We’re at a time of great danger and we need everyone to be fully aware to be able to resolve the terrible problems created by a greedy and heartless system.