Goya Drawings

You Always Learn

The Museo Nacional del Prado brings together the best collection of drawings by the Saragossa-born artist. In addition, next November it will open 'Only my strength of will remain', an exhibition showcasing more than 300 of Goya’s drawings that make up a chronological survey of the concerns of an artist who was not an indulgent observer but a major satirical and critical chronicler of a turbulent society.

In Disasters of War, a mature Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (Fuendetodos, 1746-Bordeaux, 1828) offered a highly lucid vision of the War of Independence, making Disasters one of the most universal representations of barbarism even to this day. Divided into three phases — war, its consequences for the people, and criticism in the post-war period — the series comprises images of tremendous strength, black on rough paper, the only kind available in periods of conflict. The chaos implied by the theme is also conveyed by the composition, a precedent and inspiration for later works such as Picasso’s Guernica, with a different style but identical spirit.

The Disasters or the Caprichos are perhaps Goya's best-known works as a printmaker, but from 20 November 2019 until 16 February, the Prado Museum is showing Goya: Drawings. Only my strength of will remain, covering a period that goes from the Italian Sketchbook (1771) to the albums produced in Bordeaux. If one thing characterizes this exhibition is the approach to the most personal work of an artist who, throughout his long life, was a court painter, a successful printmaker and a portraitist, among other things.

Goya never got rid, nor sold, his sketchbooks and drawings, his early tapestry cartoons, the rarely-seen preparatory drawings for the frescoes at the Basilica de El Pilar and for his first etchings, produced in the 1770s. Drawing was a constant in the painter's life from the beginning of his career, which was already far from academic conventions, until his last days in Bordeaux. Only my strength of will remain, curated by José Manuel Matilla, Chief Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Museo Nacional del Prado, and by Manuela Mena, takes visitors on a captivating journey through the evolution of Goya as a sketcher, from Italy to his last works in France, and throughout the troubled war years.

From enlightened satire to the bloodiest violence

For the observer, the drawings in the Sanlúcar Sketchbook [A] (1794-1795) are the first examples of a Francisco de Goya capable of creating in a few strokes a sharp chronicle of the day-to-day life of a society that he sees in decline. The second part, the Madrid Sketchbook [B] (1795-1797), anticipates the themes that would define Goya's later work: witches and distortions as a metaphor and description of evil and ignorance, as well as a marked satire on the clergy.

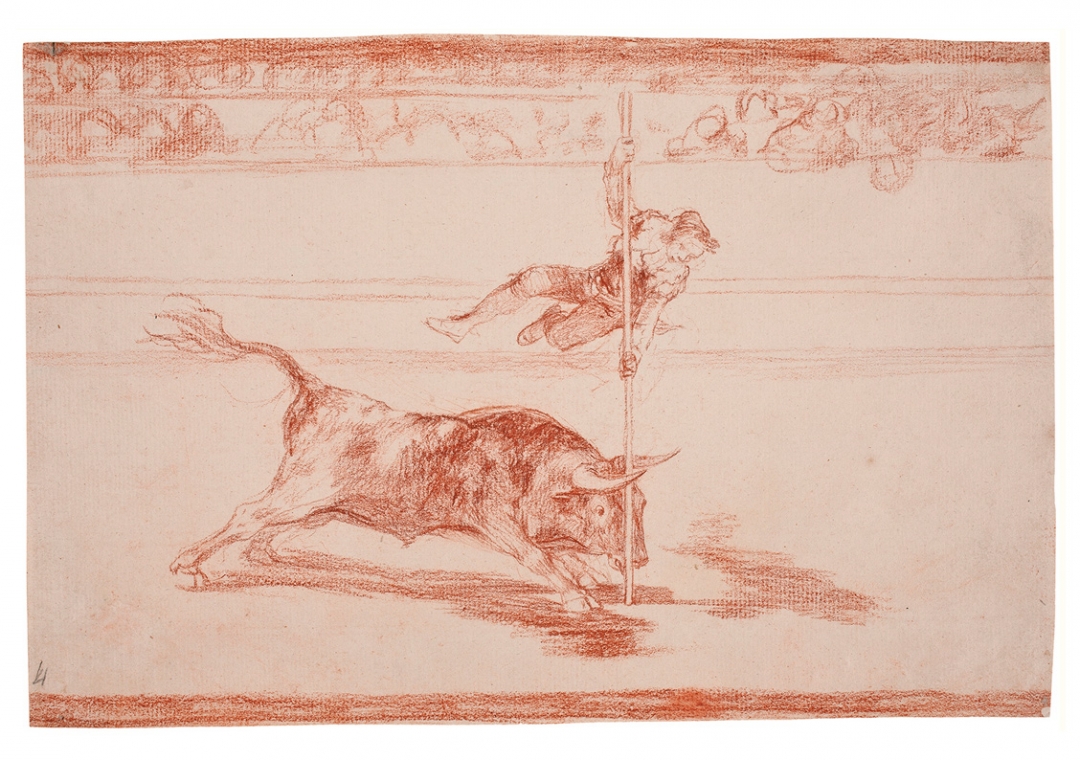

Dreams (1797) are the stylistic prelude to the Caprichos print series, published in 1799. In both instances, satire pervades compositions that are more intricate in their apparent formal simplicity. Executed with precise pen strokes, this technique allowed for subsequent detailed prints in aquatint, etching and dry point. Both series —the first coming out of the second— dissimulate, under the guise of strange and deformed figures and beings, the social themes that were the main concerns of Enlightenment thinkers. Ignorance and bad education, vices rooted in society, deception and the abuses of power: themes that are still present in the work of illustrators and artists today. Goya executed them in ink and later on he employed red chalk for the preparatory drawings exhibited in the Museo del Prado.

The thematically varied Sketchbook F (1812-1820) shares with Disasters of War (1810-1815) a stark representation of violent situations, in which poverty and tragedy are depicted without reserve. That violence is also present in the series on bullfighting, Tauromaquia (1814-1816). Beyond a first interpretative layer, a superficial chronicle featuring Goya’s recurring majas and bullfighters, his matadors are shown facing impossible and bloody feats.

From the end of the war to Bordeaux

By the end of the War of Independence, Goya was weary and critical of crowds and mobs, which he represents as an unformed mass. The drawings of this phase depict mythological beings already present in Dreams and Caprichos: the Black Borders Sketchbook, the Old Women and Witches Sketchbook, and Follies also deepen into old age, particularly that of women, the last of the great themes analysed by Goya.

When Ferdinand VII was reinstated on the throne, Francisco de Goya moved to Bordeaux, where he lived since 1824. A year later, in December 1825, the painter wrote, in a letter to the exiled Joaquín María Ferrer, the lines that give the title to this exhibition: “Be thankful for the poor writing for I have neither good sight nor a steady hand, and neither pen nor inkwell, I lack everything and only my strength of will remains.”

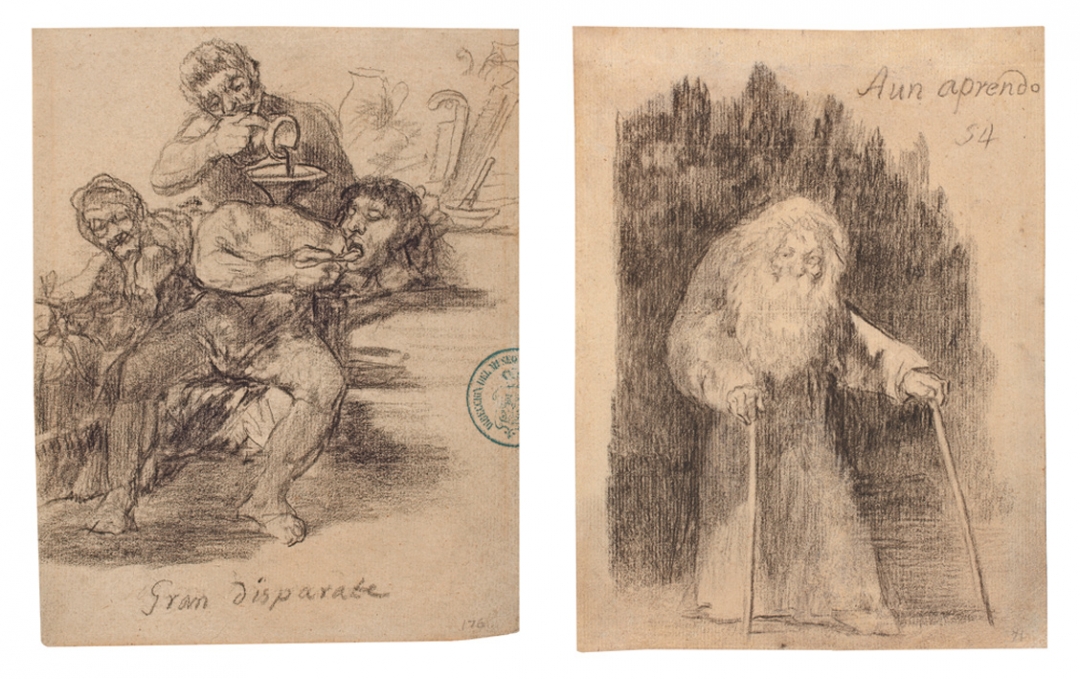

Goya continued working on his drawings until the end of his life. Despite the artist’s age —he was 78 years old upon his arrival in France— the Bordeaux Sketchbooks [G and H] show a shift from a satirical to a grotesque tone in addressing major themes in his oeuvre, such as human falsity, individual and group violence, and madness. The artist even experimented at this period with new techniques such as lithography. The drawing closing the exhibition, I am still learning, belongs to this last series and somehow summarizes the character of the enlightened old artist.

'Great Folly' and 'I Am Still Learning'. Black crayon, on laid paper. 1824-28. © Courtesy of Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid