Isabel Muñoz

The essence of being human

The lights and shadows of being human. Those are the elements that Isabel Muñoz, Spanish National Photography Award, has been capturing with her camera to delve into our true essence. Recently chosen as member of the Academy of Fine Arts, this photographer is back, within the framework of PHotoESPAÑA (20th June - 28th September), with the installation ‘Somos Agua’ at the Antiguos Depósitos Pignatelli in Zaragoza.

Isabel Muñoz (Barcelona, 1951) has been a professional photographer for four decades and has spent her entire life capturing light with her gaze. Her work, experimenting with platinum printing and innovating with unprecedented techniques, like nacarotipia or coralotipia —using seashell and coral powders—, has been recognised with two World Press Photo Awards and the Spanish National Photography Award, among others. Her commitment to the suffering of others and the planet has turned her career into a living testament of the lights and shadows of being human.

At the age of 13, you bought your first Instamatic camera. How do you remember your beginnings as a photographer

Although I've always thought I started at that age, I’ve realised that I started taking photos with my mind much earlier, because I’ve always loved observing other people’s feelings. The search of humankind has always been with me. The first photography course I took was at Photocentro, in Madrid, with Ramón Mourelle and Eduardo Momeñe. It was really creative and free, an effervescent era.

Dance was a big part of your childhood and adolescence. How did it influence the development of your talent?

I believe that dance was part of my destiny, but I couldn’t dance professionally because they didn’t let me at that time. I still dance today. Over time, I started dancing differently, I analysed why and translated that passion into photography. I think dance talks about us, about the diverse cultures within humankind, about how we are and how we move.

“The most important thing is emotion because an image that isn’t able to convey anything, that doesn’t tell a story, doesn’t interest me”

What’s more important to you in photography: beauty or emotion?

I think the most important thing is emotion because an image that isn’t able to convey anything, that doesn’t tell a story, doesn’t interest me. In fact, for me, the image exists when another observes it. I’m interested in light, darkness, for that image to be useful and for it to convey something through emotions. If you don’t achieve that, bad news.

How would you define talent?

Talent is a blend of many things: genetics, empathy, learning —you can educate your gaze—, but if there’s no feeling behind it, it doesn’t work, and that doesn’t only happen when taking a picture or telling a story. I don’t believe talent is only related to how you see the world, it’s an intrinsic part of human beings.

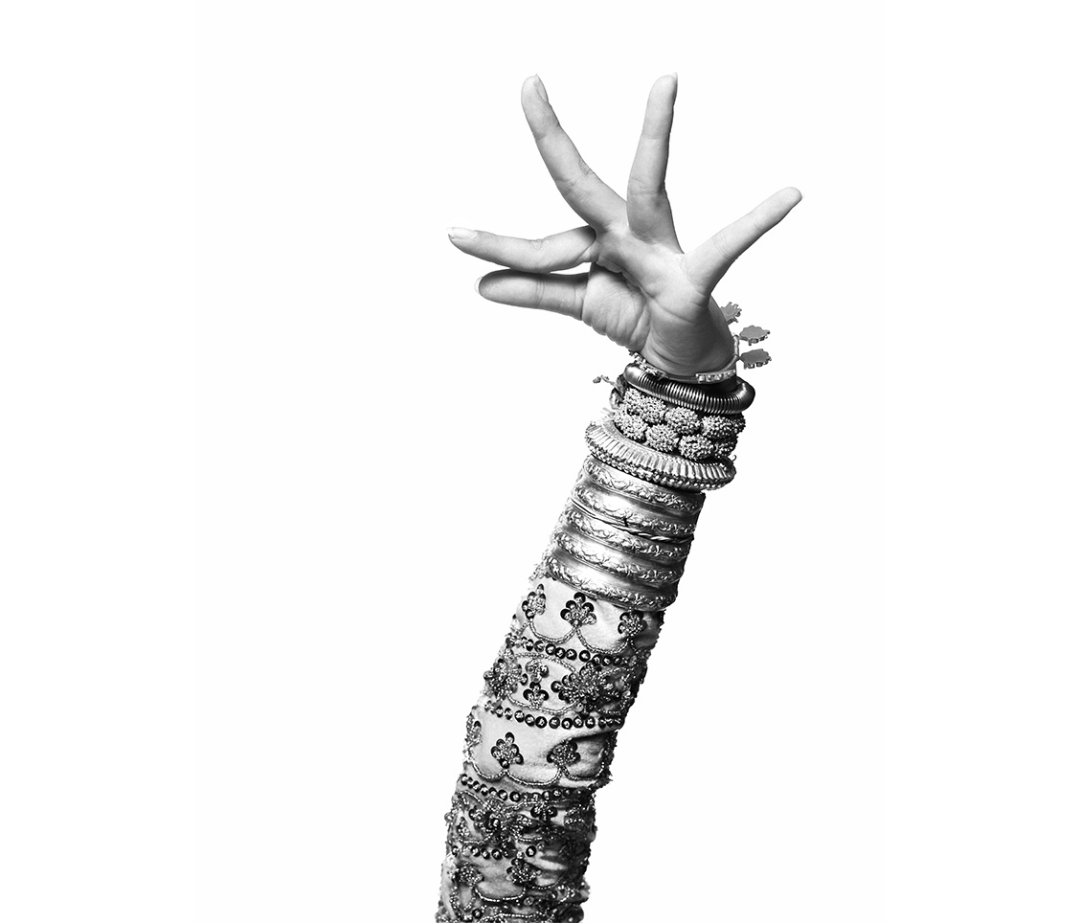

The arm of dancer Pisith Pilika has turned into one of her most iconic images. © Isabel Muñoz

Your passion for dance made you photograph flamenco, tango, and Cuban dancers... Until you reached Cambodia in 1996 and your photography changed. What happened?

That trip to Cambodia, where my idea was to photograph the Khmer dance, was a voyage of discovery. There I met Kike Figueredo, a Jesuit priest who’d do anything for the local people. I remember a dinner with him and photographer Gervasio Sánchez, talking about landmines, that changed me. I was thinking about taking photos of heaven when there was hell in Cambodia. When I saw the suffering of those landmine victims, that boy who’d just had his leg amputated without anaesthesia, Sokheum Man, I opened my eyes to a world I hadn’t explored, the world of pain that is present in our lives.

On that trip you also took one of your most iconic photos: the arm of dancer Pisith Pilika. What does that image mean to you?

Thanks to Kike Figueredo I was able to gain access to the Phnom Penh Royal Ballet to capture Khmer dancers. It’s a slow dance, with hand gestures that convey stories and traditions, which was almost lost. Dictator Pol Pot ordered that all teachers, including music and dance teachers, to be killed. Three elderly dancers survived who, after the fall of the Khmer Rouge, taught this ancient dance. That’s where I met Pisith, who was a beautiful and exceptional dancer, and I took that unposed photo of an improvised arm gesture. Years later, Pisith was forced to become the lover of Hun Sen, the prime minister of Cambodia, and his wife is suspected to have arranged her murder due to jealousy, although the crime was never resolved. I always say that that photo is like my locket, a way of remembering suffering and impunity.

Of all your works on human pain, which has been the most difficult?

The work I did about women used as weapons of war comes to mind but bearing testament to the gangs in overcrowded jails was also tough. Human suffering is infinite and after photographing it, after knowing it, you’re never the same. To be able to overcome it, when my heart is so wrung out that I need to fill it again, taking on a dance project helps me. Human beings are capable of the most beautiful and the most terrible things.

The ‘Mujeres en el Congo’ project condemns the situation of women in that African country. © Isabel Muñoz

Have you ever asked yourself if condemning things through photography is useful?

It’s a recurring question, and I’ll say that the answer is yes. Many small voices make one large voice and its power for change has been proven. Thinking that what I do is somehow useful gives me life. For example, after the Mujeres en el Congo exhibition in Kinsasa, the Congolese government itself opened an investigation into the kidnapping and raping of girls or the use of women as weapons of war. That turns into a driving force.

In recent years you’ve taken photographs of nature with an environmental message. Is it a way of condemning climate change?

When you show nature in all its glory and tell its story, you raise awareness. In a way, human beings try to change when they realise they’ve done something wrong. But you can’t defend something you don’t love, so that’s why my work talks about nature’s ability to regenerate if we leave it alone.

“Human suffering is infinite and after photographing it, after knowing it, you’re never the same”

Tell me about Somos agua, the installation we can see in Zaragoza as part of PHotoESPAÑA.

Photography as we know it isn’t enough for me, I need videos, texts, sounds, everything that provides knowledge. That’s how Somos agua came about, with free diver Ai Futaki. It’s an installation that the audience is involved in, it was exhibited at the Lázaro Galdiano Museum last year and can be seen now in Zaragoza. I believe PHotoESPAÑA has changed photography in this country: it takes it out onto the street and, also, bets on new generations of photographers, which don’t have it easy.

Which are your recent and future projects?

I’m still technically researching printing means that have a smaller environmental impact. And that’s where Manolo Gordillo comes in, a printing alchemist with vast knowledge about printing and silk-screen printing. I asked him: Can you print images on seashell powder? And that’s how we made the first ten nacarotipias (seashell prints). At the Kyotographie event in Japan, I wanted to convey a message about how global warming and sea pollution cause coral bleaching, and I created my coralotipias (coral printing) with that material. Creatively, my upcoming projects include researching the origin of human beings in Göbekli Tepe (Turkey) to talk about spirituality. When did homo sapiens start believing? Why was nature the first thing they believed in? What made them transcend or share that spirituality with their tribe?