Since opening on the 17th of April, Espacio Iberia has welcomed dozens of guests with one thing in common: their infinite talent. Talent that has inspired all the people who have sat there to listen to them.

Seeing the world through the eyes of others, even a murderer, allows us to check ourselves. This is the journey writer Mónica Rouanet takes the reader on in her latest work: ‘Nada importante’. A disconcerting story guided by almost real characters and delicately narrated mind-blowing scenes. Crime novel, indeed, but at another level.

Hot social topics, high stakes, and characters that seem as real as life itself explain part of the success of Mónica Rouanet (Alicante, 1970), one of the biggest revelations in Spanish literature in recent years. The author is busy promoting her latest work, Nada importante (Roca Editorial, 2022), a story that forces us to reconsider the role that men and women take on in society, sometimes without realising it. Crime novel? Psychological thriller? In her opinion, the best thing is for each reader to come to their own conclusions. Many of us agree on one thing: her storytelling is compulsive.

Once upon a time... how did everything start?

Writing is something I’ve done my entire life, according to my mother, but fiction came later. At the age of 19, I was in a traffic accident and, after waking up from the coma, I couldn’t remember absolutely anything —like Minerva, the protagonist of my latest novel—. So, I had to completely rebuild my identity and recreate everything my life had been up until then. I did it through photos, Super 8 films, conversations with family and friends —people who I’d just met—. I slowly started to remember... What I’ll never know is if those memories have been borrowed from others or are my own memories that have come back.

And how did you take the leap to publishing your fiction?

In 2012, I finished writing my first novel, El camino de las luciérnagas. I sent it to several publishers and didn’t even receive a reply, so I decided to self-publish on Amazon, which was just picking up in Spain at the time. “Do you think I’ll sell 100 copies?” I asked my husband. Suddenly, within a week it joined the list of 100 most-sold books, the following week it climbed into the top 20, then the top 10... Until it reached number one. That’s when publishers started calling.

“Empathy isn’t only standing in another’s shoes but embodying them and seeing the world from their perspective”

Where do your stories come from?

I take everything in as I’m walking down the street. I make up the lives and conversations of people depending on their gestures. Those images are like flashes that trigger a story. For example, El camino de las luciérnagas came from a conversation with my father: “Oh, I’d have loved for you to have met my friend Atanasio Cuervo,” he told me. I quickly started to imagine what the childhood of someone called that would’ve been like: “Atanasio, don’t cross the road”, “Atanasio, what kind of grades are these?”... I wrote a chapter and months later recovered that character; in that case, a simple name led to everything else.

The protagonist of Nada importante is related to your period of amnesia. But why did you choose domestic violence as the backdrop?

During the pandemic, we started to watch old series at home, like The X-Files. In one episode, agent Scully asks for information on a suspect. The police officer pulls out the file and says: “He served a sentence in Iowa. For sexual assault and drugs. Nothing important.” And I thought: Has he said “sexual assault” and “nothing important” in the same sentence? And I realised that if I had seen the series in 1994, which was when it came out in Spain, maybe I would have thought the same. The sad thing is that it still gets downplayed today in certain cases.

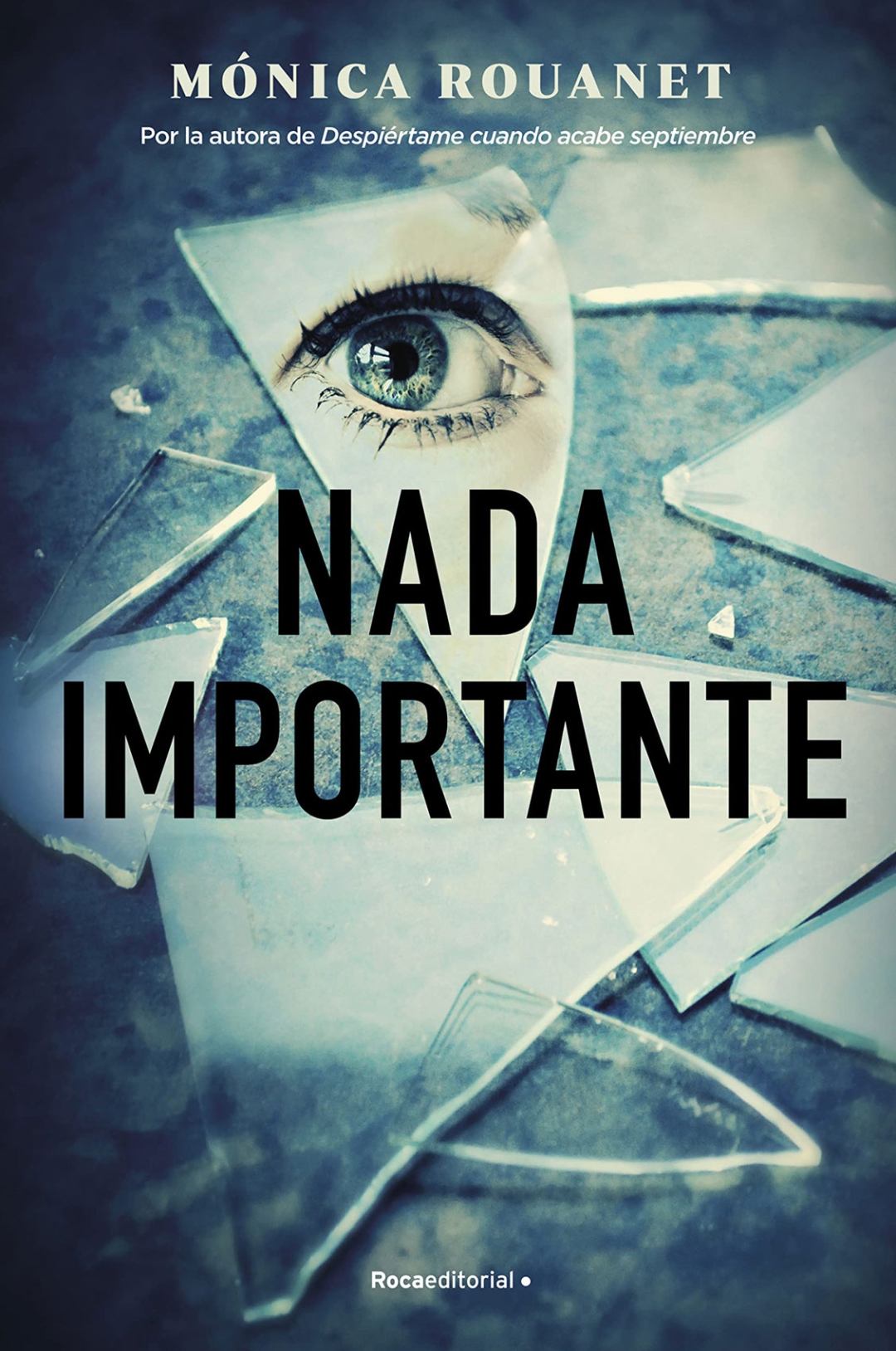

Cover of ‘Nada importante’, the latest novel published by writer Mónica Rouanet. © Roca Editorial

Domestic violence, child pornography, mental illness… Your books touch on delicate topics, how do you manage to describe certain scenes so delicately?

I’ve always said that I just write what I’d like to read, so I just describe what is really necessary for the story to unfold and the reader to understand. There’s no need to get into the thorny details. I guess that my years as a social worker [Mónica spent more than 20 years working with people at risk of social exclusion] have helped me to develop that sensibility. Empathy isn’t only standing in another’s shoes but embodying them and seeing the world from their perspective.

One of your strong points are your characters, who turn into completely real people.

When you’re immersed in a novel it’s as if you live parallel lives: your characters go with you everywhere; it’s not that they talk to you, but they are constantly in your head. And for the reader, they seem real because I don’t describe them or tell them what they like… I bet you don’t know what colour Minerva’s eyes are. I only offer information regarding their systemic bearing and some relevant data —this comes from psychology, I admit it [as well as holding a degree in Pedagogy, she has also studied Psychology]—, and the reader makes the characters their own. Once I write a novel it’s no longer mine, it belongs to each reader who sees it from their own perspective.

“When you’re immersed in a novel it’s as if you live parallel lives: your characters go with you everywhere”

Patricia Highsmith used to say that for crime novel writers to be involved in their books they needed to identify or empathise with the criminals. Do you also feel this way?

Absolutely. With the all-knowing narrator that I use in Nada importante, I force myself to look into the minds of all the characters and to tell the story of each chapter from a different perspective, including that of the murderer. In those chapters I hope that the reader despises the character, even though for a millisecond they might even identify with him. Because it even happens to me. And that’s what it’s about as well: making us think about why this happens to us.

Writers work with words; which are the must-haves that make up narrative talent?

When you write, non-verbal communication ceases to exist, and you have to share everything with words. Finding the right words that allow you to show more than tell. Because we can all tell a story, but only a few are able to show it with words. That’s where literary talent lies.

And more generally, what is talent for you?

Talent is a gift you receive, undoubtedly, but you also have to work hard and practice daily. The most important thing is knowing how to identify it, but the education we receive often prevents us from doing so.

“The most important thing is knowing how to identify the talent, but the education we receive often prevents us from doing so”

What are you focusing your talent on now?

Due to the Gata Negra festival, this summer I published a serial short story co-written alongside other crime novel authors on social media. That led to the idea of creating, alongside a partner, Book Noir Books, an online platform which will be launched in November. It’s a pre-ordered box that includes the work of a renowned or emerging crime novel author, signed and/or dedicated by them, some merchandising, literary recommendations, and the chance to take part in book clubs and creative writing workshops. The goal is to promote reading this genre in Spain.

Let’s take a little advantage of your talent: give us a novel ending (crime novel, of course).

She left the premises where she’d interviewed the writer and the last thing she said was still ringing in her ears: “Mind the buses.” When she got to the traffic light, she stopped in front of it and saw how a boy looking at his phone started crossing while it was still red. The bus ran over him and carried on its way... [It goes without saying that the author of this interview jumped into a taxi as soon as she said goodbye to Mónica].