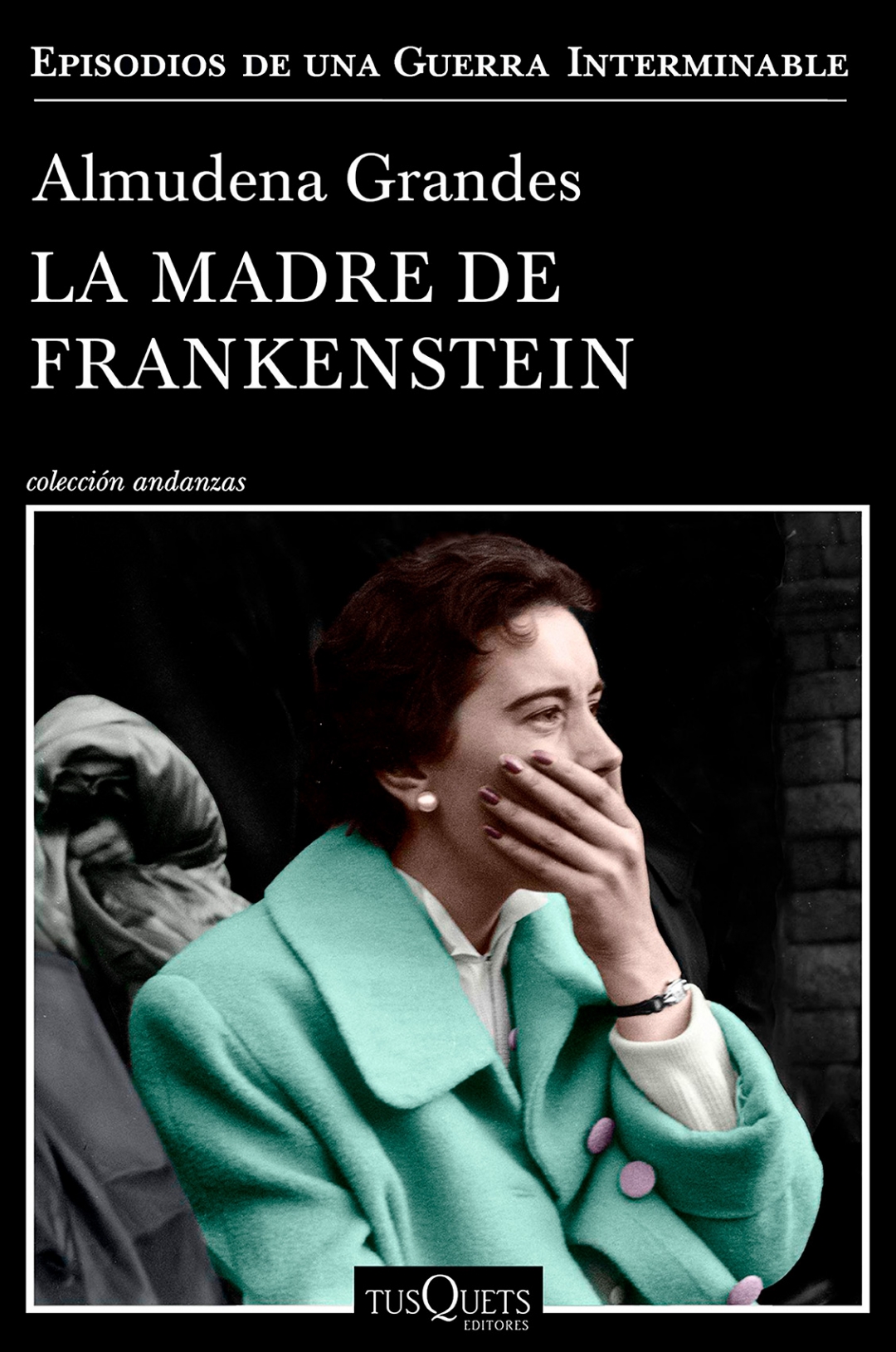

Almudena Grandes

Journey to the Women’s Asylum

The writer brings back the crime of child killer Aurora Rodríguez Carballaira in ‘La madre de Frankenstein’, the new instalment of her series dedicated to the post-war era where the reader is submerged into the suffocating and chauvinistic Spain of the 1950s.

Almudena Grandes (Madrid, 1960) returns to bookshops with La madre de Frankenstein (Tusquets), the fifth and second-to-last instalment of this solid and ambitious literary project called Episodios de una guerra interminable, which began in 2010 with the publication of Inés y la Alegría.

In this case, this is the story of a psychiatrist that, as a child, overhears the confession of a woman who assures she has killed her daughter. That woman is Aurora Rodríguez Carballeira and her daughter Hildegart Rodríguez is the child she conceived in order to improve the human species. Fact and fiction, once more, in favour of a great story of love and friendship, drafted in a way that everything you read is true, a literary truth.

You say that you’ve written this novel for all those women from the 1950s that didn’t have any opportunities.

Yes, I wrote it with them in mind. The 50s were a dark and difficult time for all Spaniards because the concurrence of the catholic church and the Francoist state, what we call National Catholicism, was even worse for women. The 50s were an era where women were ruined, spoiled, an era where everything was a sin and all sins were a crime; where a woman’s own body was her main enemy, because she couldn’t wear short sleeves, go bare-legged, have friends... Well, you could have friends, but you had to treat them like the gasman, because if you were walking down the street and approached a man, gave him a pat on the back or laughed with him, that was considered suspicious.

The story happens within the walls of an asylum.

It’s an asylum for women, the outskirts of the fringe, where nobody cares for those who live there because they are women and, to top it off, mentally ill. At the time Spanish society was completely divided, snobbish, strait-laced, and you couldn’t do anything outside of the social constraints that you belonged to since birth and breaking that rule could bring you permanent disgrace. I think that that suffocating atmosphere outside was condensed and solidified within that asylum microcosm. That is, Spain, in the 50s was also a bit like an asylum, an asylum within an asylum.

Cover of ‘La madre de Frankenstein’, by Almudena Grandes, published by Tusquets Editores

The lead character in your novel is real, I guess that was the starting point.

When I published The Ages of Lulu (1989) I went to all the bookshops looking for my book, which is the favourite pastime of all new writers. On the new table I used to see a book called El Manuscrito encontrado en Ciempozuelos, which was the clinical analysis and medical record of Aurora Rodríguez Carballeira. I had seen Mi hija Hildegart [film by Fernando Fernán Gomez] and knew the story. I must say that the arrogant, proud and hateful assassin here was an unarmed woman in a room in the asylum that continued to rave about her destiny as the saviour of the world and that, since she was no longer able to become pregnant, she made rag dolls with huge penises, which she looked at for hours to convey her thoughts and bring them to life with her mind.

What did you find fascinating about her?

Aurora met all the conditions to become the model of the new woman that this country needed. She was an intelligent, cultured, self-taught woman, educated beyond the constrains of feminine education. She was rich, so she was independent and able to move freely, she didn’t shy away from public life, she wrote books and articles, gave talks... She transferred all this capital to her daughter so she would be the new Prometheus, her instrument and messiah, she was ruined by mental illness. She shot her three times in the head and once in the chest. She killed her and then turned herself in naturally, saying that she’d killed her daughter because she hadn’t turned out right. She destroyed her own work. She was an assassin and a paranoid woman, and everything about Aurora after the crime fascinated me. I’ve been thinking about it for thirty years.

“Aurora met all the conditions to become the model of the new woman that this country needed. She was intelligent, cultured, self-taught, independent...”

So, when you planed your Episodios project, she was there from the start...

Yes, she was. Because after The Frozen Heart I didn’t know what to write, and I started a film script that didn’t end well, and also a play called La madre de Frankenstein. Out of all my theatrical failures, it’s the one that’s turned out the best, because when I was editing this play, I realised that what I had to do with this character was write a novel.

I wouldn’t call it a failure...

That play has led somewhere, because I believe that everything that’s made with love, even if it’s a mistake, is good for you. When the time came to write the novel, I read the play and realised that she was inside of me, as was Germán, the psychiatrist. In fact, he was already in Las tres bodas de Manolita. That’s why I’ve written this novel so quickly, because Aurora and Germán were already there. I concluded that I needed another character, a nurse: María Castejón.

María Castejón is one of the main characters in this novel, in fact, she ends up taking over the plot with her impossible love story with Germán, that psychiatrist that returns from exile in Switzerland and constantly says “this isn’t Switzerland”; if Germán returned to Switzerland now, would he say the same thing?

Well, we’re still far away, but differently; he comes back from a rule of law, a developed, democratic country with guarantees. He gets to Spain and doesn’t understand what’s happening, he feels like his country rejects him. Now, Spain isn’t like Switzerland because as Pepe el Portugués [anthological character in the novel, the professional revolutionary] says, Switzerland is a neutral country, and, for better or for worse, Spain has never been a neutral country. In any case, when it comes to lifestyle, Spain is more like Switzerland now than in the 50s.