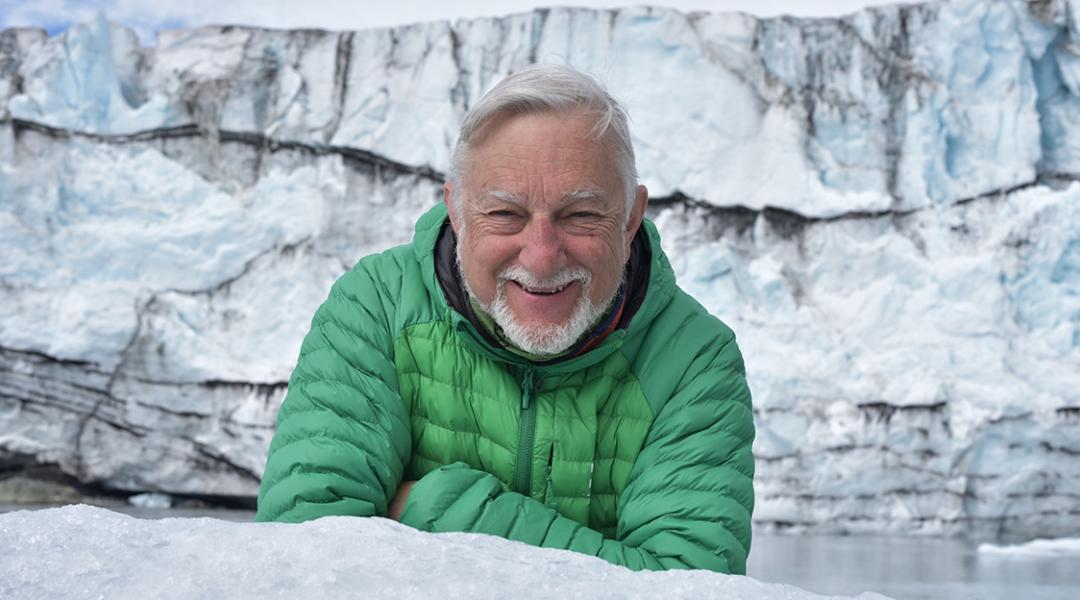

Javier Cacho

A human being in Antartica

Antarctica has become a second home for Javier Cacho. This Spanish physicist, whose studies on the area’s ozone managed to slow down the hole’s growth, has received a recognition that he feels particularly proud of: an island named after him. Just like his dear Antarctic explorers, Cacho is already part of the history of the place where, he admits, he discovered “the greatness of humanity”.

Scientist and writer Javier Cacho (Madrid, 1952) spent his childhood and adolescence “with his head in the clouds” and he became a physicist to be able to study the atmosphere and, specifically, the ozone. This would determine his career as a researcher at the Spanish National Commission for Space Research (CONIE, current Spanish Space Agency) and the Spanish National Institute for Aerospace Technology (INTA), since his analysis of the atmosphere coincided with the appearance of the hole in the ozone layer in the 1980s. His scientific career took him to Antarctica, where he worked as the head of the Juan Carlos I Antarctic Base. As well as writing the first Spanish encyclopaedia on the gas that protects us, Antártida: El agujero de ozono, Cacho has published biographies of the great polar explorers, (Amundsen, Scott, Shackleton, and Nansen), where he reveals the lights and shadows of the frozen continent.

Your career as an atmospheric physicist led you to specialise in a little-known gas at the time: the ozone. Why?

I remember a professor talking about ozone and it seemed fascinating to me. I decided to ask him more about this gas and he recommended going to the library of the Spanish National Institute of Meteorology. I spent many hours there and in four months I prepared a thesis of more than 100 pages on the origins and measurements of ozone. When I went to present it to him, the professor had left the university. The secretary of the department recommended that I hand it in at the office of professor Joaquín Catalá, the greatest expert in Atmospheric Physics in Spain, and that’s where I thought my adventure with ozone ended.

But that’s not what happened.

No, because that professor decided to talk to me. “I’ve been reading it. Would you like to work with us?”, he asked me. And that’s how I started. It was when INTA purchased the first atmospheric ozone measurement equipment.

When did the ozone reach the news?

When the ozone was massively destroyed in Antarctica, which had been measured since 1956. The English had also realised, but didn’t dare to say it, and the same for the Americans. They were such strange data that nobody believed them. The instrument measuring the ozone had a parameter that gave an automatic error whenever the data provided extremely high values, but it was happening: the ozone layer was being destroyed. The hole was growing larger, and we understood the dire consequences of this problem. We didn’t know if it would remain over the Antarctic or if it would extend across the planet and we’d be left unprotected.

“The ozone hole gave us a global view, proving that our actions had consequences”

At that time, you landed in Antarctica to analyse the phenomenon. What was that first trip like?

Spain was organising its first scientific and oceanographic expedition. I was accepted and landed there, with my instruments, to take on-site measurements of what was happening with the ozone. We observed that the ozone hole only occurs during southern spring. On the following trips, in 1988 and 1989, we took an instrument that measures nitrogen dioxide because we realised that it plays a significant role in the generation of the ozone hole.

And, at least in this instance, scientists managed to raise awareness within society. Was this a question of talent?

It was more a case of good luck. When I returned, I found that people were interested in my work and there was a lot at stake. Until then, pollution was considered something local; nobody could imagine that compounds emitted into the atmosphere in the northern hemisphere could travel 20,000 km over the years, massively destroying the ozone. The ozone hole gave us a global view, proving that our actions had consequences everywhere. Now we’ve internalised this, but at the time my friends would joke that we were “apostles of the ozone”.

What is the current situation?

From the year 2000 onwards, the size and depth of destruction of the hole started diminishing; we believed it was the first environmental success. It seemed like we were on the right track, but in the last two years two large new holes have appeared and we don’t know why it has intensified. We’re experiencing climate change and we still don’t know how this is affecting Antarctica. Discovering this will take longer than we thought.

An island in Antarctica is called Cacho Island in recognition of his work in the area. © Courtesy of Javier Cacho

Which sacrifices or hardships have you had to face in your work as a scientist?

The hardest thing was always leaving my family for months at a time to travel to Antarctica. It was really hard on my daughter. She thought of Antarctica as a monster that would take her father away. When she was nine years old, I wrote her a story to help her understand what it was like living there. I told the story through a Siberian husky puppy in Las aventuras de Piti en la Antártida. We’ve just published it again with a small publisher, Serendipia.

In return, an island in Antarctica named after you.

Yes, a tiny island that I feel immensely proud of: Cacho Island. Seas, mountains, glaciers, coasts… have been named after the great Antarctic explorers. The fact that my name sits beside theirs makes me even prouder. It came about thanks to a Bulgarian initiative: they wanted to thank me for my educational work regarding the Antarctic spirit because when I was head of the Spanish base, I helped their scientific delegation.

For years you’ve researched the great polar expeditions: do you believe that we can promote scientific talent?

I believe it’s important to talk about Antarctic explorers because they’ve written down pages in history of incredible beauty, with their successes and failures, from which we can learn valuable day-to-day lessons related to solidarity, tenacity, and perseverance. All of that seems key to me and it’s what I try to reflect in my books.

“In Antarctica, I found solidarity, cooperation, and science. In that difficult landscape you discover the greatness of humanity”

Are there explorers that history has forgotten?

Yes, they’re not as famous as Amundsen, Scott, Nansen, or Shackleton, despite being important, because they don’t have that epic story behind them. There was a German expedition that left at the same time as Scott’s, but they didn’t achieve anything grandiose that made them famous. They wrote seven volumes of scientific work, but the heads of state weren’t interested in that. There are more expeditions whose stories deserve to be told because they show the tenacity of humanity. I’m preparing a book about them, and I hope to finish it in May next year.

What role did women play in that phase of exploration?

They were the truly forgotten ones, because at that time it was really hard to find sponsors. There was one woman, Louise Arne Boyd, who didn’t need them because she was a millionaire. She fell in love with the Arctic and worked on exploring it, first for pleasure and then to map it out. Another great female explorer was Josephine Diebitsch Peary, who got to the Arctic with her husband, also an explorer, Robert Peary, and even had a daughter there. “If Inuit women give birth here, why shouldn’t I?” she said. I’m researching them now because we must defend their role: their experiences were equally as fascinating as men’s and their female sensibility provided a different and enriching vision of polar exploration.

Do you think Antarctica brings out the best in people?

Antarctica is a place of extreme beauty and harshness simultaneously, there’s no room for mistakes, and you can die. Above all, I found solidarity, cooperation, and science. Helping each other was common, even if it meant putting your life at risk to save a colleague. There, you’re surrounded by human beings and where they’re from or what they’re like doesn’t matter. In that difficult, sometimes oppressive landscape, you discover the greatness of humanity.