Helena Rohner

Jewel-shaped Digital Poetry

She was one of the first to apply porcelain to jewellery. Not long after, she did the same with wood. Now, many of the pieces made by Helena Rohner are 3D printed. A new craftwork era for an entire industry that the designer unfolds first-hand.

Both the influence of the Canary Islands, her homeland, and minimalism are traits that are represented in her jewellery. But if we had to highlight one of her personality traits, it would be her intuition. With more than 25 years of experience, her instinct has been her guiding light. When nobody thought that porcelain was appropriate for jewellery, Helena Rohner (Las Palmas, 1968) used it. Now, a whole generation of artisans bases its products on this material. Something similar happened with wood. Right now, her production is focused on 3D printing, which has allowed her to discover a more sustainable and environmentally-friendly dimension to design. This creator reveals to us how craftwork is conveyed in the digital era.

Your ability to apply materials and play with light points to scenes from your homeland, the Canary Islands. Is it something that inspires you or is it part of your DNA?

I think that we carry experiential and aesthetic baggage with us... The Canary Islands are undoubtedly the organic and essential part of my creations. Their strong sea, clear sky, stones, absolute colours, their bright light. But there are others. My father was a Protestant Swiss in love with Scandinavian design. Aesthetically, I grew up with that minimalist and simple vision of furniture. Furthermore, my mother is from the Canary Islands and is passionate about craftwork. Since I was young, I have been surrounded by textiles, baskets, clay... With time, you realise how much all of that influences you. I’ve been very fortunate. I hope my children can have a similar experience.

You’ve inherited your creative gene then?

We live in the same world, but creativity is part of how each person sees reality. Everything has influence, but in the end, it depends on your cognitive abilities, on what you are capable of creating.

When did you realise that jewellery was your way of exploring this creativity?

When I was 17 years old, I studied jewellery in Florence for a year, but I ended up enrolling in Political Sciences, after encouragement from my father. He was an absolute feminist and always taught me to be independent, and I thought that it was essential to have a good degree to achieve this. I’m thankful to him, because studying Politics has helped me develop my management and leadership skills, and even my powers of persuasion.

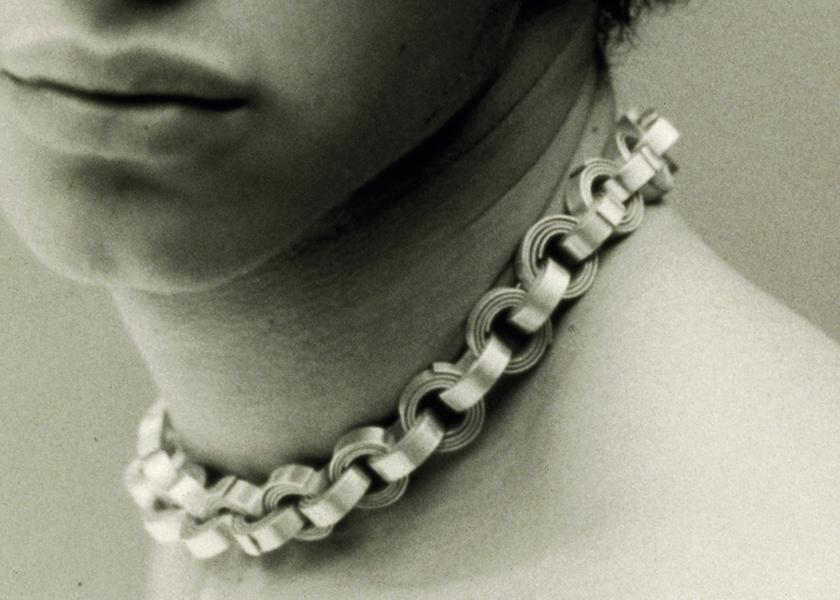

Images of Helena Rohner’s 2019 Autumn-Winter collection. © Azahara Fernández

And how did this adventure begin?

When I finished my degree in London, I met Jacqueline Rabun, an artistic jeweller who made pieces that placed value on handmade work. That was when I realised you could make a living out of this. I had just turned 22. Through her, I started to sell to Barneys New York. Before I knew it, I had orders for 500 pieces that I had to produce by myself. That was when I created the company. It was all really intuitive. Afterwards, I started selling in Japan, and then to Paul Smith.

The brand emerged with an absolutely international calling. Is this still so?

Yes, in fact, a few days ago I was looking through our list of retailers and our distribution network abroad consists of 40 retailers, while in Spain we only have 20. And the international ones are big. Nevertheless, I’ve never had a business plan or a development approach. I’ve learnt on the job. The same as I’ve done with jewellery, materials, and now, with 3D printing. It’s a constant challenge.

Where did you get the idea to produce your jewellery with 3D printing?

Through Instagram I discovered Comme des Machines (a business from Biscay that produces 3D printing). I saw that they were doing some interesting things and I really liked them. Again, it was very intuitive. I wrote to them and they came to Madrid to meet me. We’re on the same wave length regarding ideologies such as sustainability. It’s a very symbiotic bond and I feel that it’s also extended to jewellery.

Is 3D printing very different to traditional production?

I draw a sketch or make a wax mould and send it to them for production. But they’re also really creative and bring a lot to the table. For example, in my last Brancusi collection I started working with shapes, but I couldn’t get the right closure, and they came up with the solution: they created magnets hidden inside balls, there are no hooks. If you think about it, it’s a very technological, but also manual world. They call it digital craftwork or poetry. They can take one night to produce a piece of jewellery, and then it’s polished by hand.

Are you limited with regards to materials with this kind of production?

We work with PLA (polylactic acid). It has some projection limitations. But in the two years we’ve been applying it, progress has been tremendous. At the beginning, the pieces needed to have a flat surface to rest on during the process, and now we can even make knots mid-air.

Images of Helena Rohner’s 2019 Autumn-Winter collection. © Azahara Fernández

Would you say that this is a new form of craftwork?

It depends on how it’s treated. We work with biopolymers, although there are people who use polluting materials. But beyond biodegradable fibres, 3D printing has another benefit: you can produce just what you need.

What’s the biopolymer’s composition?

It’s usually yucca, potato or corn. In fact, when you drill it or handle it, it smells like vegetables. But it also works with clay, ebony or cement. For the next summer collection, we’ve created a biopolymer that includes copper. It can be polished and weighs like metal.

You’ve recently presented a pouffe collection with Gancedo, is there anything you haven’t done?

Sculpture, but I don’t dare to try it yet. I’ve designed crockery, furniture, candles, lampshades and even textiles, which will be released soon. I’ve just launched some textiles with Iloema. This is one of my passion projects. It’s a company that wants to make the traditional embroideries from Toledo known. They’re developing contemporary pieces based on tradition, that tell the story of how women talk about culture through embroidery.

What’s stopping you from trying sculpture?

In the end, design is art to be used, but taking the leap to make a piece that is merely decorative is something else. I still feel that I need to free myself or take one step further in my development. I think you need an even more pronounced narrative.

Returning to your product, you design jewellery that men like, what’s your secret?

We create jewellery for the type of person that is devoted to art, culture, subtlety and, in a way, individuality. It’s aimed at a timeless man, who is released from the logic of masculinity. The designs come from the female collection, but with more refined lines. Some people like Quim Gutiérrez or Benicio del Toro have made the pieces their own. This is my biggest challenge.

Images of Helena Rohner’s 2019 Autumn-Winter collection. © Azahara Fernández