Since opening on the 17th of April, Espacio Iberia has welcomed dozens of guests with one thing in common: their infinite talent. Talent that has inspired all the people who have sat there to listen to them.

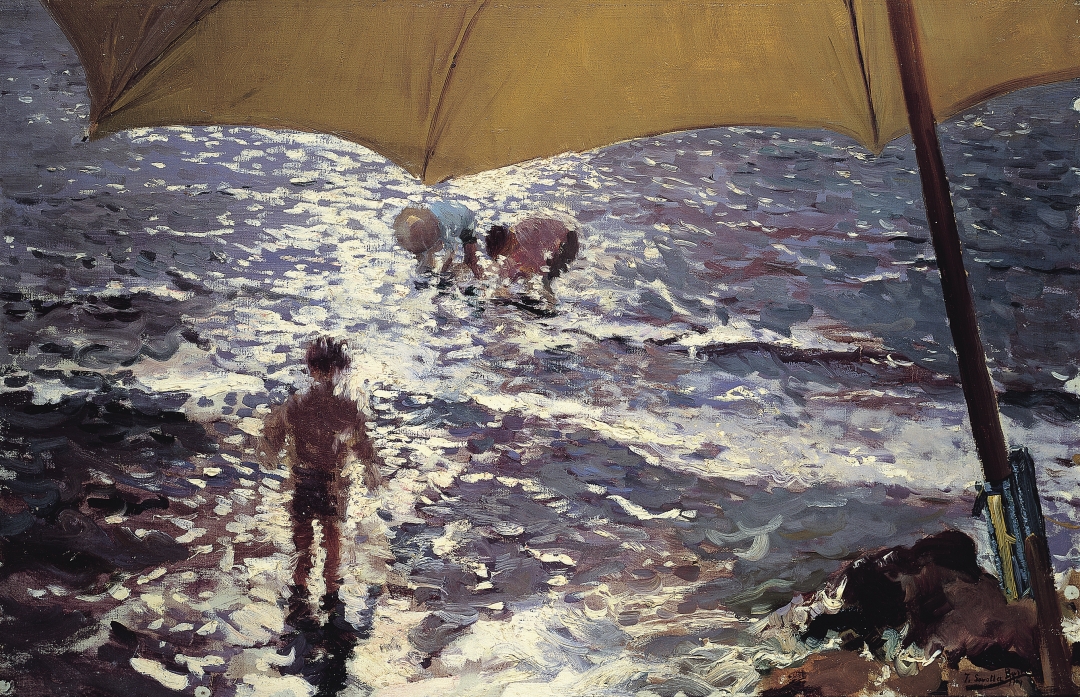

All artists harbour an obsession that acts as inspiration, as a spiritual blood bank. Sorolla didn’t have one but two—light and his family. The talent pervading his depiction of the customs of his time and the intimacy of his likenesses turned him into a complete, perfect artist. The National Gallery in London is showing a unique retrospective until 7 July.

With the over 60-work exhibition Sorolla: Spanish Master of Light, the Valencia-born painter returns to London 111 years after his first show there in 1908, which, incidentally, was not very successful.

But for Christopher Riopelle, the exhibit’s curator, the work of Joaquín Sorolla (Valencia 1863-Cercedilla 1923) returns now to the British capital with honours, recreating “the intensity with which he looked at the world, evidenced by his obsession to render the effect of light on skin and cloth, water and nature”. A passion in which his wife Clotilde and his three children feature prominently.

Sorolla portrayed his wife and muse in over 2,000 paintings, mostly home and outdoor scenes with their children. But he also extolled her femininity, as evidenced in the canvas Female Nude (1902), an outstanding work for two reasons—it is one of the paintings that best represents Sorolla’s use of light, but it was never confirmed Clotilde was the sensual woman lying on rosewood silk.

“The obsession to render the effect of light on skin and cloth, water and nature characterize the work of Sorolla”

Seascapes and landscapes abound in his body of work. Sorolla painted life on the beach—clad in a suit, shoes and a hat—in canvases such as Clotilde and Elena on the Rocks at Jávea (1905), Snapshot at Biarritz (1906), Valencia Beach in the Morning Light (1908), Walk on the Beach (1909), and After Bathing (1915).

He also painted patios and gardens, places of calmness and leisure. The combination of architecture, vegetation and fountains appears on several canvases, including ones depicting his house in Madrid, now the Museo Sorrolla, La Alhambra in Granada and El Alcázar in Sevilla, siestas in the shade and children playing.

Joaquín Sorolla passed away at the early age of 60. Some say he died out of exhaustion, others claim he had inhaled too many pigment chemicals. As a legacy, he left an inimitable and genuine purple shadow on impressionism.