Andoni Canela

Sleeping among wolves

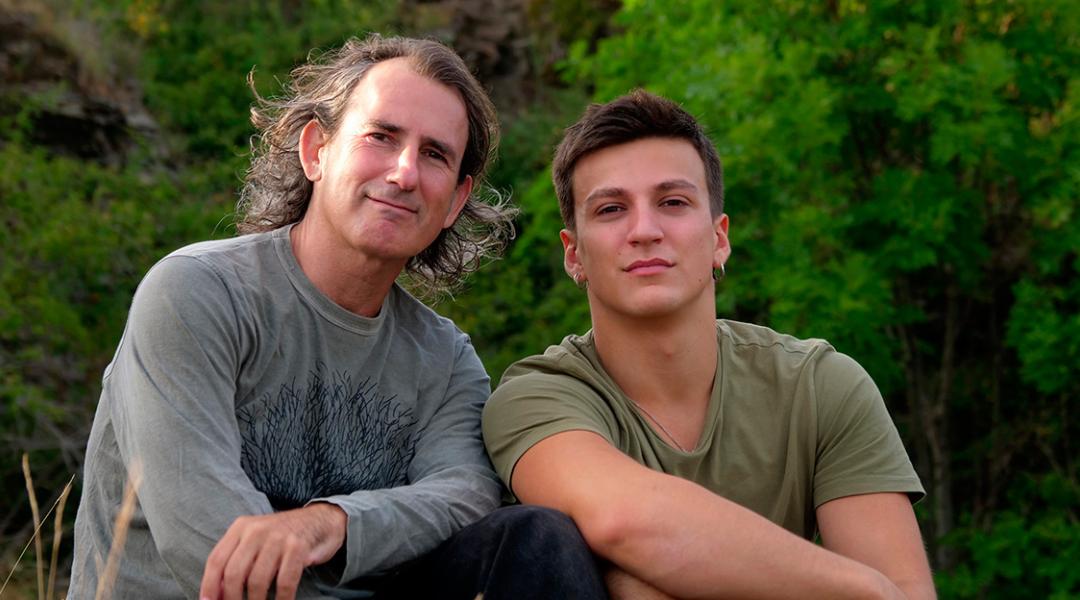

Photographer Andoni Canela’s love for nature stems from his childhood, when curiosity led him to look up information in an encyclopaedia he had at home. He went from chasing animals on paper without getting off the sofa to doing so camera in hand covering many kilometres around the world. A passion he proudly tells us he has inherited from his son Unai.

What makes journalist, photographer, and documentary maker Andoni Canela (Tudela, 1969) stand out is his proverbial patience. Able to walk for weeks, track for days and wait for hours in silence, without moving, for the wild animal he’s looking for to appear, Canela specialised in nature photography, pointing his lens at endangered species and publishing his photos in media such as National Geographic, BBC Wildlife, or Newsweek. In 2017, he premièred Looking for the Wild, and in 2021, Panteras, environmentalist documentaries that he has also turned into books like Sleeping Amongst Wolves or La llamada del puma, and exhibitions like En tierra de linces or El Ártico se rompe. Canela is currently back chasing the wolf, his favourite animal, with his camera, for a project he will be spending the following years on.

How is a nature photographer born?

My father had a camera that he used to lend to my brother and I. So, the first photos I took at the age of 12 or 13, as well as being of my family, were of the flowers and birds that inhabited a small vegetable patch close to the Ebro river that we used to go to. My career after that, photographing nature around the world, comes from innate curiosity. At home we used to read a lot, we had the famous Encyclopaedia El Hombre y la Tierra and many adventure novels that also influenced me. I think that combination of nature, animals, and travel literature left a mark on my career.

You taught yourself photography. Do you think it’s a profession that one can learn with practice?

During my Journalism studies, at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, I didn’t have photography lessons until my third year, but by then I’d already learnt the basics through photography technique books and magazines like National Geographic. I was interested in great photographers like Ernst Haas, Thomas Mangelsen, and Michael Nichols. At the time, my photography experience consisted of trial-error. Even though I later studied at the College of Printing in London, I don’t think that studying an official photography course is essential; today, thanks to the Internet, you can practically learn astrophysics.

“The greatest difficulty that comes with photographing endangered animals is that the encounters is fleetingly or nightly”

How do you choose the animal you’re going to photograph and what is your research process like?

The choice is quite personal, unless it’s a commission. I can also go back to some themes, like felines, because I think I still have work to do. The research process involves a long period of documentation, with all the bibliography I find, to understand their behaviour and learn how to approach the photography. The more information you have, the less you despair.

One of your most successful books was Sleeping Among Wolves, a species you have photographed again. Why?

I spent a few years working abroad with endangered felines, but the wolf is the species that I’ve spent the most years on. I’m amazed by their intelligence and their ability to adapt; they live in areas with little food or shelter, they are hunted, and even so, they manage to survive. Delving into this species is a challenge because there are few photographic documents that portray wolf packs, how they move and how they work.

What’s the hardest part about photographing wild animals?

They can hear and smell you, so you can’t get too close. Often times you don’t even have to hide because you’re not going to be that close, you just need to wear camouflage clothing and stand among the vegetation. You can also choose high places for greater visibility and, from there, sense where they going to move to because they depend on food. For example, in summer, wolves are predictable because they breed in a specific area, but when the wolf cubs have grown and they start to move around freely, days can go by without seeing them. This puts your patience to the test.

Nevertheless, the wolf hasn’t been the most difficult animal you’ve photographed.

No, the one that took the most time and effort was the Snow Leopard in Tibet. The first close sighting happened after walking for three weeks, keeping the camera batteries stored close to our bodies so they wouldn’t freeze. You have to keep humidity and condensation from preventing you from taking photographs at key moments.

Many of your works portray ecosystems on the verge of extinction. Why?

I look for a protagonist to tell a story. When you’re aware of such strong biodiversity problems, where man has decimated populations, I look for the human and animal behaviours that have led to that situation. The greatest difficulty that comes with photographing endangered animals is that you either don’t find them, or when you do it is fleetingly or nightly.

“You may be born with a special sensibility for photography, but that doesn’t determine your future because you have to care for it and work on it every day”

Your son Unai, co-star in your documentary Looking for the Wild, now follows in your footsteps. What has his progression been like?

I’ve seen how his gaze has matured and how his interest for travelling, nature, and animals has grown. His curiosity is key. I also value his efforts when taking photos and videos, as can be seen in the work we did together (Panteras) for four years. During the pandemic, Unai started his first solo documentary (Entre montañas), which has led him to be the youngest documentary maker at the San Sebastian film Festival. Some people travel far to take photos, but Unai did the opposite and spent a year documenting his closest surroundings.

Do you think talent is inherited?

You may be born with a special sensibility for photography, but that doesn’t determine your future because you have to care for it and work on it every day. A photographer with less intuition or sensibility can go far if they work hard. In terms of photography, talent isn’t such a determining factor; being curious about life will have a greater impact.

And finally, can you tell us about the project you’re currently working on?

I’ve spent two years and have two more to go to finish my project on the wolf. I don’t think I’ll be able to present it, which will be photographic and documentary, before 2025. In the end, every time I face a project, even if I already know the animal, it’s like starting from scratch.