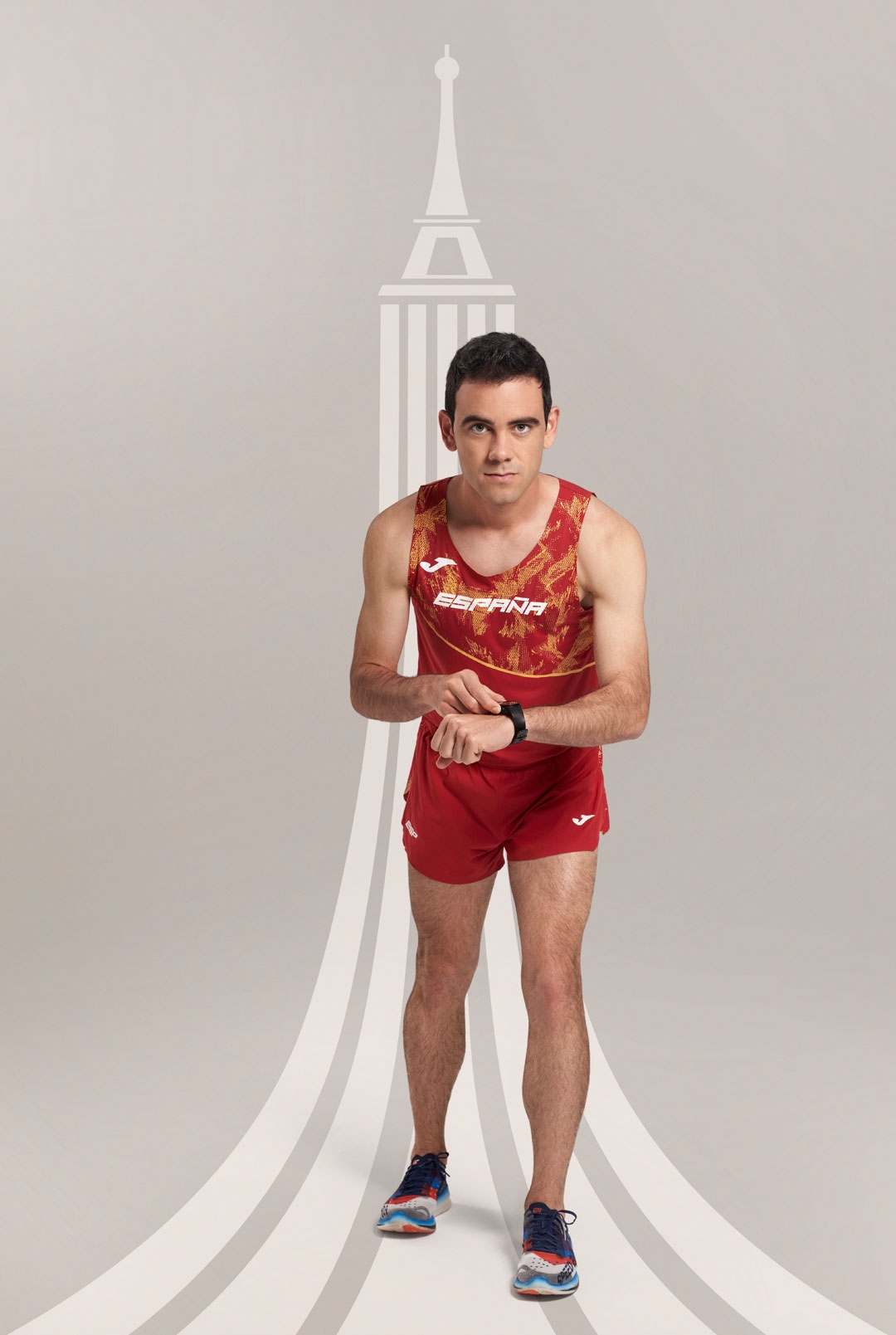

Diego Gª Carrera

The man of race walking

Race walking, a quintessential discipline in athletics —in the Games since 1908— is in danger. One of the most talented race walkers in Spain, Diego Gª Carrera, admits as much. But all is not lost. As if he were a modern Don Quixote, this athlete defends the survival of race walking and, from his position, he invites federations, institutions and amateurs to add their voices to a simple but effective claim: RESPECT.

The adjective “quixotic” suits Diego Gª Carrera (Madrid, 1996), the race walker, quite well. We don’t say this because of his slimness, typical of any race walker, but rather because of his passion for defending the discipline he’s dedicated his life to. He declares that race walking is in danger and demands RESPECT, in all caps. At the latest edition of Madrid Marcha, a race that brings together the best race walkers in the world and where Diego acts as sports director, attendees wore a bracelet featuring this word in Spanish. Despite everything, this athlete, who is fully aware of the real giants race walking is up against, seems optimistic and his recent appointment as member of the Athletes’ Commission at World Athletics —the world governing body for athletics— means he’s close to where decisions are taken. Strictly in terms of the sport, and despite his disappointment at the recent World Athletics Championships in Budapest, Diego hopes to improve on the sixth place he achieved in Tokyo at the Paris Games.

You started out running and have ended up walking; when did you realise you were better at race walking?

I started out running because that was what I was best at within athletics and race walking came about a bit by chance. When I was 14, I didn’t qualify for the Spanish Championships and a friend suggested I try race walking. “I’m sure you’d be good at it,” he said. And, indeed, I was better at it than I thought. With little training I was able to improve a lot, which I was no longer able to achieve with long-distance disciplines. I needed to prioritise performance and chose race walking.

Speaking of talent, what does it mean to you?

Talent has a lot to do with skill, whether in sports, art, or any other field. But talent isn’t always related to the result; because talent is the raw material, but then for it to bear fruit, you need to add hard work and dedication.

“Talent isn’t always related to the result, you need to add hard work and dedication for it to bear fruit”

Race walking is one of the most long-standing athletics races, but it seems like it’s being called into question recently. Would you say that it’s in danger?

Yes, we must be realistic and we’re facing a dangerous situation. This time, monetary interests —races that make more money always receive more attention— added to sports factors, like the recent changes to distances, but also political considerations: English-speaking countries don’t stand out in race walking, but they are the ones in charge at international institutions. Therefore, countries with a more long-standing tradition need to step forward. This cocktail of factors means that we’re in danger if we’re unable to show off our strengths.

Spain has had (and still has) great champions in your discipline. Is race walking missing greater recognition in Spain?

Always. But even within athletics, it’s hard for race walking to make headlines. This year we have made them, but it required winning lots of medals [race walkers Álvaro Martín and María Pérez won four gold medals at the recent World Athletics Championships in Budapest]. We have to buck the trend and start to place value on race walking. Everyone within Spanish athletics benefits in the long run from race walking getting the recognition it deserves.

A few weeks ago, you were elected member of the Athletes’ Commission at World Athletics. What will your role be and what does this mean to you?

Athletics includes many different disciplines and it’s usually hard to find common ground. When one of those disciplines isn’t represented, we tend to forget about it and that’s why it’s important to be there. The situation with race walking is a top priority because we’re at a tipping point, but regardless of that, I’ve done athletics as far back as I can remember and being present where the interests of athletes are defended, and decisions are taken is a huge responsibility for me.

Diego Gª Carrera hopes to improve on the sixth place he achieved in Tokyo at the Paris Games.

You’re one of the promoters of the Madrid Marcha race. Which is its purpose and why do you wear a bracelet featuring the word RESPETO (respect)?

I’m from Madrid and I’d been thinking for some time that the city could host a race that would raise awareness of the huge talent for race walking there is in Spain. But, beyond that, we want to proclaim that spectacular race-walking events that attract the general public can indeed be organised; in short, to challenge the prejudices surrounding the discipline with facts. And I believe we’re achieving this. We have the RESPETO (respect) motto because, in recent years, race walking hasn’t been treated the way it deserves, it hasn’t been a priority for federations or institutions.

As we’ve been saying, the prospects of race walking aren’t the most promising. Even so, would you encourage a young athlete to try it?

Its prospects aren’t the best, but all is not lost yet. If we stick to the present, race walking continues at the Games and that’s an incentive for any athlete, and many people are also willing to defend it. There’s no reason to not give it a chance and I encourage people to try race walking and enjoy it.

“Everyone within Spanish athletics benefits in the long run from race walking getting the recognition it deserves”

Before the World Athletics Championships in Budapest, you declared: “I’m doing some of the best training in my life.” But things didn’t go as you expected [39th in the 20-km race]. What happened?

Sports aren’t science and things don’t always go according to plan, both for good and for bad. For many years I’ve been an athlete who’s had great competitions that weren’t backed by great training sessions. Now, however, I have to deal with the flip side. In Budapest, things didn’t turn out but, fortunately, this has happened a year before the Games, so there’s time to turn this situation around.

Despite that blow in Budapest, are you still optimistic about the Paris Games?

My next big goal is performing well at the Spanish Championships, to confirm my qualification for the Games (I’ve qualified, but the selection hasn’t been made yet), and gain the confidence that will allow me to get to Paris with the chance to fight for everything. In Tokyo I was in the lead group almost until the end and I was really close to winning a medal [Diego came 6th]. In Paris, I want to surpass that level.

Music is another of your passions. In fact, you play the trombone and are studying a Master’s in Sound Engineering and Record Production. In the future, do you see yourself more connected to the world of sports or music?

The truth is that I’m not sure. I’ve always loved music, and today I play in a jazz band and I’m really happy. But to work exclusively in music you have to do really well, and I’m still just an amateur, especially if I compare it to my sports career. I don’t like to leave things for tomorrow and that’s why I’m taking my first baby steps, but we’ll see when I retire. In fact, it could be neither music nor sports, I’m open to anything (laughs).