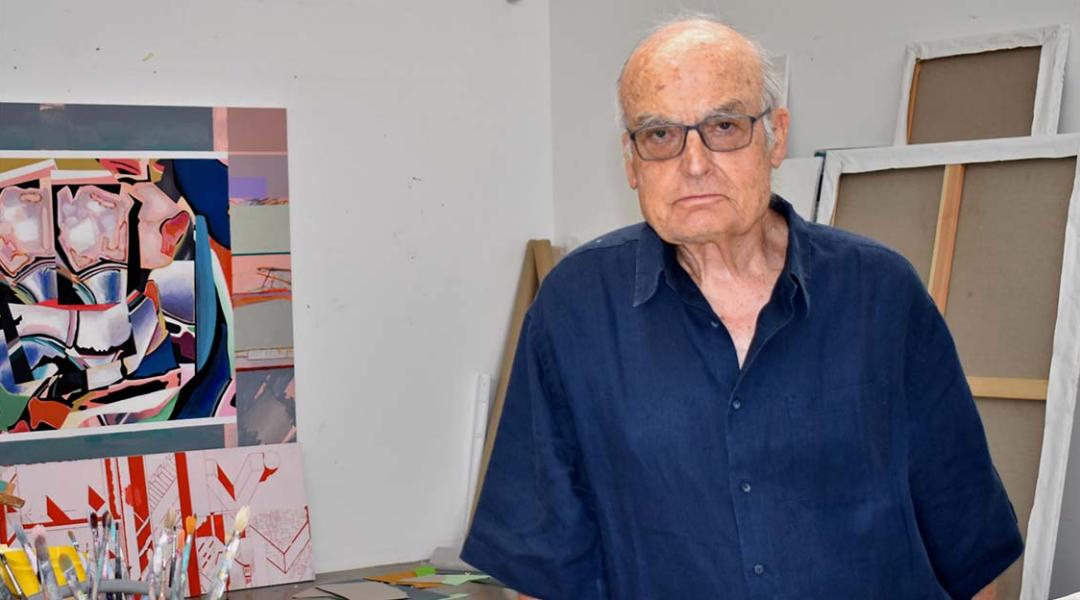

Luis Gordillo

From avant-garde to calm

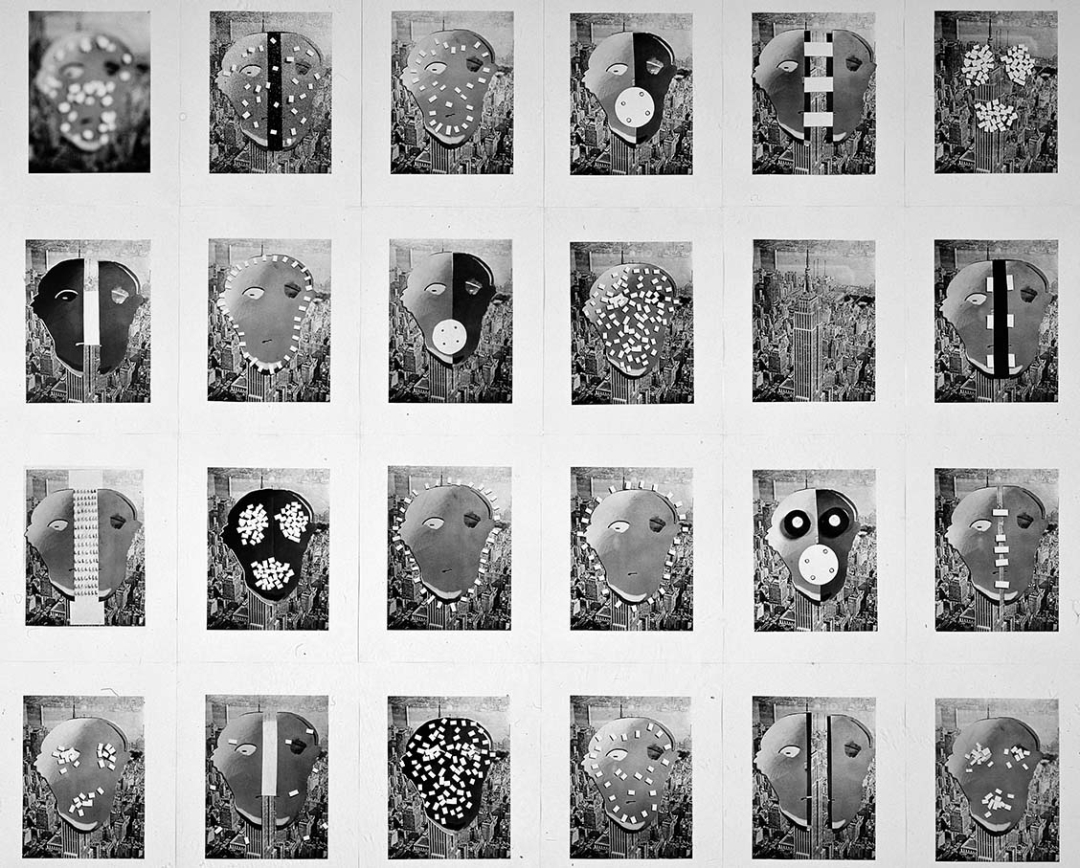

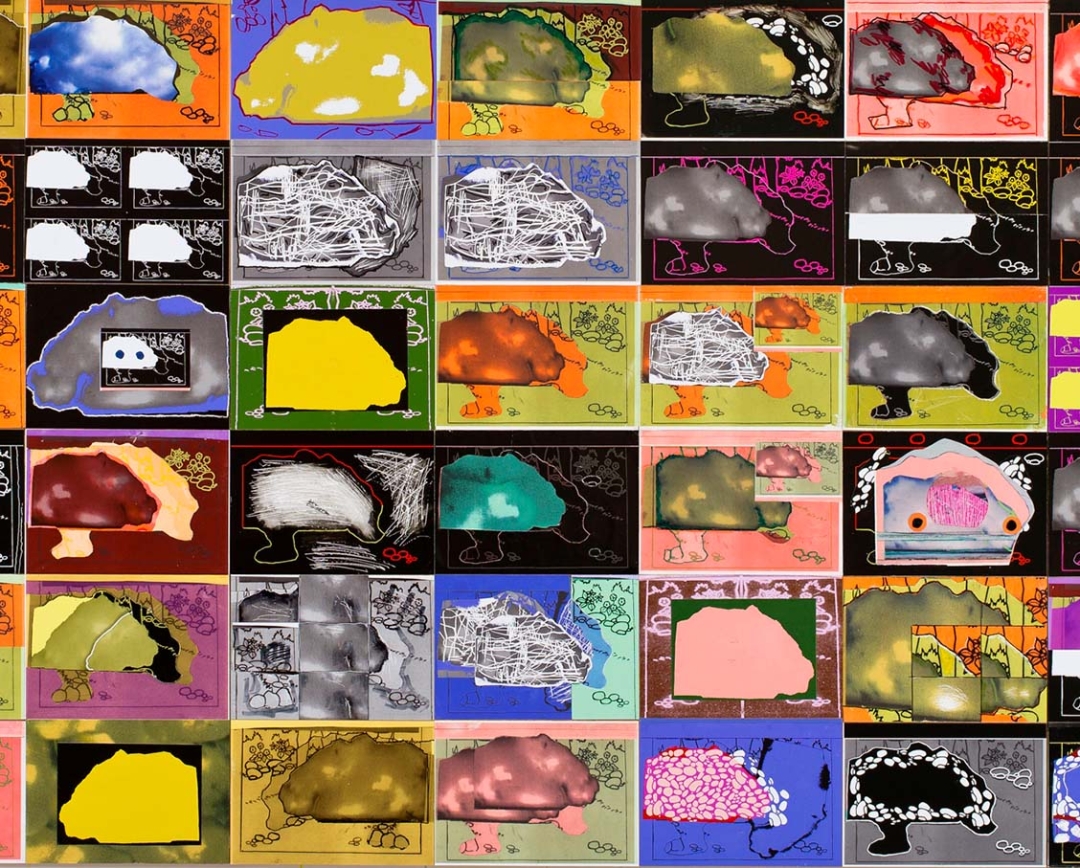

Luis Gordillo has been through several aesthetic trends as a painter and has inspired many generations of young artists with works close to avant-garde. Today, somewhat calmer, the Andalucian artist still captivates the audience with his series, ‘collages’, and paintings that talk about a colourful, ironic, and sometimes intriguing inner world. Now he’s back in his hometown, Seville, with his latest anthological exhibition: ‘Manicromático’.

“I’m quite old and I’ve been through many trends, I’ve skirted avant-garde in many cases and there comes a point where avant-garde moves away from you”, confesses Luis Gordillo (Sevilla, 1934). For some time, as he himself admits, he sails calmer seas far away from searching for new revolutions. “When you get older, you’re less eager to drive the audience mad,” he adds. His work has slowly become something more likely to be understood and closer in terms of conveying values that, in his case, are always aesthetic. “I’m a painter’s painter, my messages are aesthetic, and I don’t have political purposes.” His work, he says, “is no longer a difficult work” and, in fact, the different series that make up Manicromático, his anthological exhibition in Santa Clara in Seville, show a friendly painter, full of colour, inquisitiveness, and vitality at the age of 88. Green and turquoise blue alongside brown, pink, and almost pastel mauve harmonise with magenta, yellow, and more intense lime in a kind exercise, despite the artist reminding us that behind his works, his own psychological tensions always beat.

Luis, what have all these works together, from the 1970s until now, revealed to you?

In general, that they have a certain pop vibe. I had a pop period at the beginning of the 1960s, really orthodox and different to now, but pop can be spread with many different aesthetics. This exhibition has a dynamic, really colourful aesthetic, reminiscent of a large avenue and great performances.

Despite being series from different phases, aesthetically, they seem really contemporary.

It’s true, and odd because really, my work has changed a lot over the years. I’ve worked within informalism, especially the French art informel, then I changed to pop, and later had a somewhat geometric phase. Either way, over many periods, the soul of my art, which is really spontaneous, has remained the same. When I work spontaneously, I feel like there’s a homogeneous base throughout my work. But not in my paintings, because they’re quite far away from spontaneity.

“The truth is that I’ve always been distrustful of my work, I’ve never really believed in it”

Is there a lot of thought behind them?

More and more. If I’m honest, now I suffer a lot with my paintings because it’s a really thoughtful process. I feel like I’m doing something really technical. It’s a deeply studied, observed, and controlled work, and everything involving control requires effort. And that’s tiresome. Currently, the creative process of my paintings lasts an extended period of time. I take months and months to do one. And I don’t only make one painting, I work on several at a time: I take a break from one and move onto another. It’s like having a sort of coop full of creatures that grow and I take care of them all at the same time... And there can be quite a lot of them! What I don’t understand is how I have the patience and willingness to push myself so much.

After such a long artistic process, is there a special relationship between you and your works?

The truth is that I’ve always been distrustful of my work, I’ve never really believed in it. Over time, critics give complimentary reviews, you receive awards and, somehow, you start to believe in it. That eases my mind, it gives me confidence and calm. Furthermore, distance matures your opinion of things. Now I see paintings from the 1970s or 1980s, for example, and I suddenly say to myself: “This is better than I thought!” When I see them now, it’s as if they’re characters with their own personality which move with certain autonomy and freedom, as themselves. That feeling of the paintings maturing, seeing them, and recognising them as finished objects-characters, is really important to me.

You hate for your talent and work to be defined as mere abstraction, right?

It annoys me to no end when they say, “Gordillo is the best abstract painter in Spain”. I’ve read that many times. Some of my paintings may seem abstract, but I don’t feel like my work is abstract. First, because I add characters to my works, of one kind or another —animals, people, or comics—, and ideas that are reminiscent of living things from reality. Even now, many kinds of characters appear in my works, and even when they seem more abstract, I don’t see them that way, I consider them significant.

Does digitalisation broaden the discourse of a work?

Digitalisation is really important for painting in general because its limits are so broad. I joined the digital realm late and I’m really interested in it; in fact, some of the works in the exhibition are made using digital methods. Some time ago I worked with other imaging techniques, like silk-screen printing, for example. Methods that you can use to transform colours, the work itself, and through which, with that variation, you can find a different painting that interests you more. With the digital world, those possibilities are astronomical.

“I’ve moved away from avant-garde trends because it’s something hard to sustain when you’re in your eighties”

Luis, what’s up with Spanish talent? Why doesn’t it manage to become a role model at an international level?

Well, there are Spanish artists that are working really well outside of Spain and, in general, there’s a good average level, but it’s true that there are no eye-opening artists in revolutionary fields. I believe that for that to happen, there needs to be an important market behind it. Money works there because it gives the artist security, it gives the means to work intensely. The country’s power also matters. New York, Berlin, or London are the centres of the world.

Tell me about the impact of chance on your work, is it that important?

I’m greatly interested in it. That feeling you get when you’re making a collage and you take an image, place it on top of another and, suddenly, bang! As if it were a miracle, something that you couldn’t foresee has happened. Nevertheless, in that instant, and from that act itself, comes creative enlightenment, like lightning. That’s an example of what chance is, something incredibly active.

You’ve been a painter that’s constantly changing; where are you going now?

For the last few years, my work has been calming down. I’ve moved away from avant-garde trends because it’s something hard to sustain when you’re in your eighties. My work has taken shape and matured a lot, and perhaps it’s already made because of my age, my psychology, because of the history of the world of art itself. Perhaps I won’t change that much anymore.